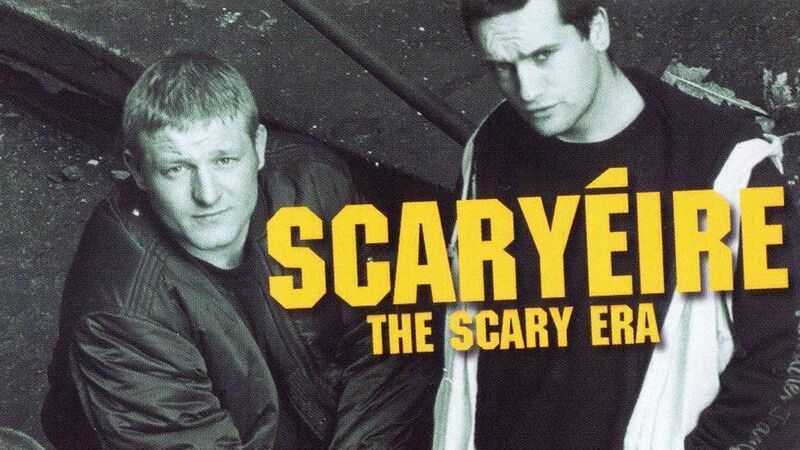

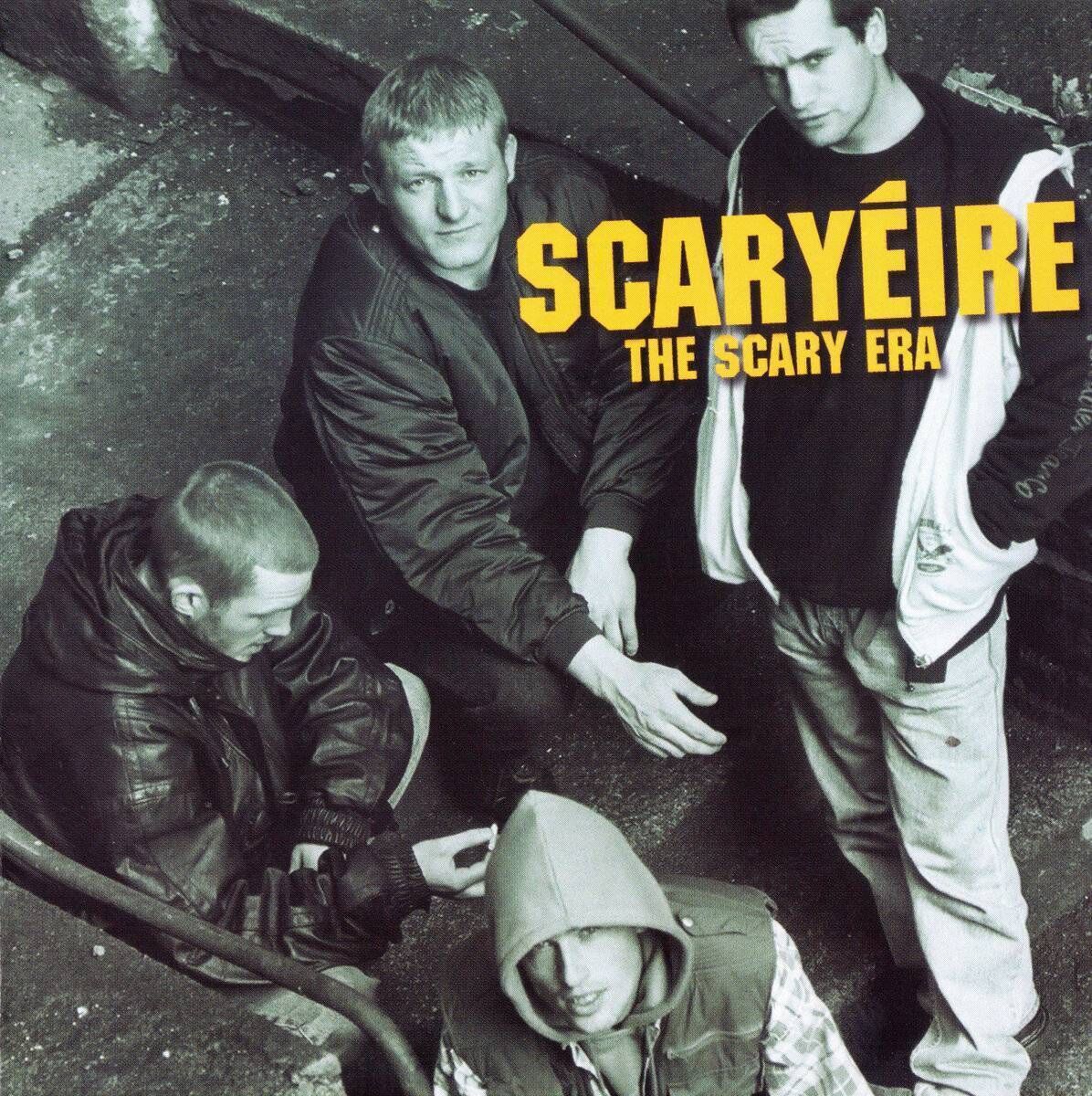

Ireland in 50 Albums, No 38: The Scary Era, by early hip hop act Scary Éire

The Scary Era, by Irish hip hop group Scary Éire.

When Scary Éire took to the Salty Dog stage at Electric Picnic in the early hours of August 29, 2019, nobody present could have guessed they were witnessing the end of not one but several eras.

Within months, Covid would plunge live music into an economically ruinous deep freeze. For Scary Éire – playing a rare reunion show after reforming earlier in the year – it was a different sort of farewell. The group would once again go their separate ways soon afterwards, and then, in December 2022, founder member James Molloy, aka beatmaster Dada Sloosh, died suddenly aged just 48.

But those losses were all in the future that night, as Scary Éire delivered a blistering set that reminded festivalgoers why they were among the most important pioneering voices in Irish hip hop – mould breakers in an era well before Kneecap, Kojaque, and Rejjie Snow.

The quartet of Molloy and MC Cainneach MacEoghagáin (Rí Rá, both from Tullamore), scratch artist Pete Mescall (DJ Mek from the Curragh), and “Mr Browne” (from Dublin) brought distinctive Irish wit and grit to gangsta rap when they emeged from the Dublin DIY scene in the early 1990s.

Making an immediate impression with their blend of Jamaican dub, turntable scratching and bodhrán playing, they were soon supporting the Beastie Boys and House of Pain. They even attracted an influential admirer in U2’s Adam Clayton – leading to an unlikely opening slot on the Zoo TV tour which in turn instigated a disastrous falling out with Island Records boss Chris Blackwell.

“There were small pockets of hip hop fans around Ireland,” recalls MC MacEoghagáin, aka Rí Rá, by email. “Most of us knew each other. We’d meet in Dublin. A lot of people linked through breakdancing and collecting music. You could get all the latest releases in Abbey Discs – we’d usually see everyone there.”

Rí Rá remembers pre-Celtic Tiger Dublin as a city brimming with creativity. “There were gigs in McGonagle’s [a famous indie venue just off Grafton Street]. There was a monthly night in the Pembroke Bar, a kind of open mic thing. We had graffiti artists, DJs, MCs. Every element of hip hop was covered in small pockets. And it was all new. Nearly every week there’d be something we hadn’t seen or heard before. Fresh is the word.”

He and Molloy grew up in Tullamore which had at that time a vibrant music scene. “Tullamore has always been teeming with musicians, from folk clubs to trad sessions. Everyone in the 1980s seemed to be in some sort of band. And we caught hip hop early on. Half of Scary Éire came from Tullamore,” he says. “We’d all known each other since the mid to late 1980s. We’d dabbled with demos in different forms, under different names. By 1990 we decided to form a band. I came up with the name Scary Éire, and we went from there.”

Within a few months, they were building a following around Dublin – word spreading among gig-goers who caught their incendiary shows at venues such as the Rock Garden in Temple Bar, or their residency at Barnstormers, a long-shuttered club above a pub on Capel Street.

“We never had a problem getting gigs. At the start you’d just ask the venue for any free dates – three or four quid at the door. They were happy enough to get the drinkers in. After a few gigs the name had gotten around, and a lot of demo tapes. We had management. We were offered a deal, and things started flying. I don’t remember any hysteria in the media or the Irish music scene at the time over rap because they hadn’t registered it. They were still clanging guitar.”

Scary Éire were skilled rappers and producers, but they also brought a distinctively Irish sense of humour – something Kneecap, in particular, have emulated. You can hear it in their best-known track, which begins with the unemployed narrator lying in bed, wondering how he’ll occupy himself for the rest of the day: “I open out the door, to go into the jacks / Me aul’ lad’s waitin’ on the landing – “Aaaagh, smack!”’

“They took something widely dismissed as novelty in Ireland and pushed it into real cultural territory,” says Odhrán O’Brien of hip hop label Golden Éire Records. “They helped set an early template for Irish hip hop, proving you could use your own accent and still be credible, without needing to cosplay American or UK delivery.”

Among their early admirers was Adam Clayton of U2, who had caught some of their shows – a connection that led to a deal with Island Records. They signed to the label in early 1993 and released later that year to instant acclaim.

“The U2 gig came about after Adam Clayton had been to a couple of our gigs,” says MacEoghagáin. “He was singing our praises, plus we were signed to the same label. The Beastie Boys was later, that would’ve been towards the end, in ’94.”

As Scary Éire were taking off, across the Atlantic Boston’s House of Pain were enjoying success with their own brand of “Irish” hip hop – though, as song titles such as showed, their idea of Irishness was painfully out of date. Nonetheless, they and Scary Éire were often grouped under the loose label of “Paddy rap”.

“When House of Pain came to Ireland for the first time, they were all shamrocks and shenanigans. We played support. And they went back with the realisation that the Irish don’t really eat bacon and cabbage every day,” says MacEoghagáin.

“Their second gig here was very different. They were shouting us out repeatedly. Listen to their second album. They dropped the “begorrah” shite. They’d probably still be looking for leprechauns if they hadn’t met us.”

Supporting U2 at the RDS in August 1993 should have been the start of a new chapter. Instead, the gig proved a disaster – magnified by the presence of Island Records boss Chris Blackwell who was in the audience, watching the shambles unfold. Halfway through the concert, rapper Mr. Browne began goading the crowd – “I can’t hear you, I can’t hear you!” – before jumpinginto the front row. Twenty-four hours later, Island A&R man Barney Cordell, who had signed the group, received a fax.

“It’s a handwritten letter from Chris Blackwell saying that with immediate effect, Scary Éire are no longer on Island Records,” he recalled in the documentary “Two teenage girls got knocked out – he landed on them.”

Cordell, who passed away in 2023, remembered the band up as "wholly original, didn’t give a shit, and brilliant”.

That was the end of their relationship with Island, but because they didn’t have the rights to their recordings, they couldn’t release any music. In 2007, they finally regained ownership and issued featuring material recorded in Dublin ( ) and in London with producer Howie B ( ).

As demonstrates, much of Scary Éire’s appeal came from wordplay ripped straight from everyday life. “There was a lot of absolute truth in the lyrics. Dole Q had actual names of places and people. I used a lot of Irish slang words, and sometimes [Irish],” recalls MacEoghagáin, who continues to release music as Rí Rá. “It was telling stories about where you were from, and what you’d get up to there. Sometimes it was just MC battle talk, but most of the time, it was pure truth.”

Irish hip hop has come a long way since then. But Rí Rá feels it’s still yet to be fully accepted. “I think it’s still, today, looked at as a novelty. When people say Irish hip hop is in the best place it’s ever been, that best place is still seldom heard outside of the country. Remember, hip hop is an import. It doesn’t export well from any other countries outside of America. The UK has had the strongest scene this side of the world, and still some of their absolute legends are unknown in the States or elsewhere. It’s worldwide but still regional. And it’s supposed to be.”

Looking back, it is obvious their Irishness – lyrics such as “Me aul lad’s waitin” – was to central to the appeal of Scary Éire.

Odhrán O’Brien of Golden Éire Records says: “Hyper-locality was part of their signature, which is a principle we try to carry through in our own records. The more specific the references, the humour, the tensions, the further the music travels. So even if they’re not always the first name people mention now, their legacy is clear. They proved that hip hop could be Irish, not an imitation, and still stand up on its own.”

- Rí Rá’s latest album, , is out now