'Songs to the Siren' gathers impressive pieces at the Model

The exhibition at the Model co-curated by Paul Hallahan, includes Daphne Wright’s 'Pig', and a self-portrait by Christy Brown.

, the new exhibition at the Model, Sligo, takes its name from a song by the American musician Tim Buckley and its inspiration from the Irish writer Brian O’Nolan. Needless to say, both are greatly admired by the exhibition’s curators, Paul Hallahan and Lee Welch.

O’Nolan wrote under several pseudonyms. As Myles na gCopaleen, he produced a long-running satirical column in the and published the Irish language novel And as Flann O’Brien, he published the iconic novels and which inspired a major exhibition Hallahan and Welch curated at Dublin Castle early last year.

“That first show we did,” says Hallahan, “we were looking at quotes in Flann O’Brien’s novels for a title, but nothing was landing.

"We had about 20 different names. And then, out of nowhere, I found an unreleased song by Jeff Buckley and Elizabeth Fraser of the Cocteau Twins. They were a couple for a while, and they wrote and sang a song called It’s only a demo, but I was just, like, wow. I sent it to Lee and he was like, OK, we'll go with that for our title.”

The Dublin Castle exhibition was spread over two rooms and was largely concerned with the dualities in Flann O’Brien’s fiction.

“In O’Brien’s books, two things can be happening at once. They can be sad and happy, ludicrous and serious, but at the same time, they will all be working together. That was really interesting to us as curators.”

When the Model approached Hallahan and Welch about curating an exhibition this year, they decided to delve deeper into O’Nolan’s concealment of his real identity.

“We were in contact with the Flann O’Brien Society,” says Hallahan, “and they’re not 100% sure, but they think O’Nolan may never have published under his own name. And knowing that, we felt that this new exhibition would have a sadder tone, and we could bring in darker works as well.”

This time, the title came more easily.

“We knew there was a connection between Elizabeth Fraser and Jeff Buckley’s father Tim, because she covered with This Mortal Coil. We said, OK, we can bring Tim Buckley in as the connection. We can close the circle. And then it ends up as a kind of father/son situation within the two shows.”

Buckley’s original version of and Fraser’s cover with This Mortal Coil, are both spellbinding. Which does Hallahan prefer? “Tim Buckley’s,” he says. “This Mortal Coil’s version is good, but it’s very stylised. I listened to it recently and there’s maybe too much wah-wah pedal. It’s still stunning, but I think with Tim Buckley, there’s definitely something very special about his own recording of it.”

One of the biggest names in is Banksy, the pseudonymous British artist who began spraying graffiti on the streets of Bristol in the early 1990s and is now a major figure in the international art world. The curators have included a painting of his called which depicts a mother and father holding hands with a child whose head has been replaced with red crosshairs.

“We’re used to Banksy deflating political or social subjects through humour. But what intrigued us about this particular painting is that it’s not humorous at all.”

The curators could have organised an entire exhibition of work by pseudonymous artists, “but that would have been too easy,” says Hallahan. Instead, they question whether O’Nolan’s “quiet sadness” and ambiguity may also be found in the work of a broad range of 20th- and 21st-century artists, including his near-contemporary: Jack B Yeats.

Fifty-two of Yeats’s artworks are preserved in the Model’s permanent collection.

“I think we'd always had it in our minds that there would be one of them in the show,” says Hallahan. “The painting we picked is small; it’s called One of the tech guys at the Model says Jack B Yeats is the boss that's never there. The aura of the Yeats family is all around the place for sure.”

Also featured is the British Turner Prize-winner Mark Leckie, whose 23-minute film features archive footage shot in Britain from the year of his birth.

“It also has a reference to an 1890s poem by William B Yeats, ,” says Hallahan. “It’s to do with the valleys and the waterfalls just behind the Model.”

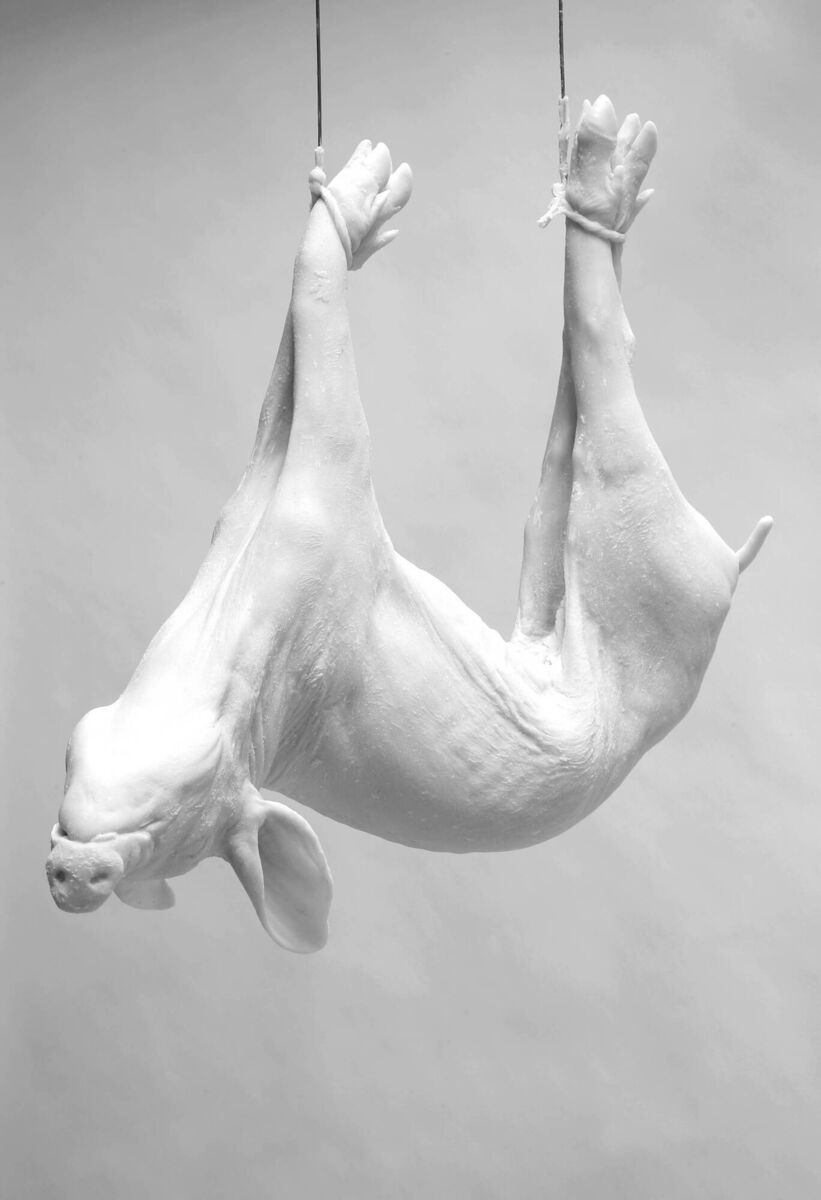

Others among the 26 pieces in the exhibition include Seán Scully’s early figurative painting, , Christy Brown’s self-portrait in oils, and Joyce Pensato’s painting, . One of the most striking inclusions is Daphne Wright’s , a marble dust and resin sculpture suspended from the ceiling.

In Dublin, where both curators live, Welch has a day job as an archivist and photographer at the Kerlin Galley, while Hallahan is a full-time artist. Despite being in demand — he had his first solo exhibition in the US, at the Maus Contemporary in Alabama, just last month, and is preparing for further shows in Westport and the Custom House in Dublin next year— he admits the job is not without its challenges.

“I’ve had a space at Fire Station Studios on the northside for the past three years,” he says.

“I take advantage of every opportunity that presents itself, and I try not to spend more money than I have. That’s basically the trick of it. But Dublin’s very squeezed at the moment.

There’s three artists in the show that have lost their studios with the Complex closing. I’m in much the same situation

"My residency finishes in June, and I don’t know where I’ll be after that. It’s bloody hard, and getting harder. I don’t know how young artists do it at this stage.”

To some, the petty bureaucracy and social conservatism that Brian O’Nolan satirised in his writings might seem almost quaint compared to the world of upheaval we live in today. But Hallahan is not so sure.

“Personally, I've got the funny feeling it's always been like this,” he says. “We just have more information about what’s going on. I think if you looked back to 1996, for instance, if you knew everything that was going on, and if that was all piped into your phone, you’d be stressed as well.”

As for whether art should engage more with politics, he thinks not.

“People might look to art for answers, but I’m not sure it has the answers. I think it’s actually more important than that. Politics comes and goes, but art is always going to be here. If you look into history, we’re not talking about the political artists of the 1890s, we’re talking about artists that were able to get above or below the politics. Dare I say, it’s like the Catholic Church. They’re not thinking in years, but in centuries.”

- Songs to the Siren runs at the Model, Sligo until March 22.

- Further information: themodel.ie; hallahanwelch.com