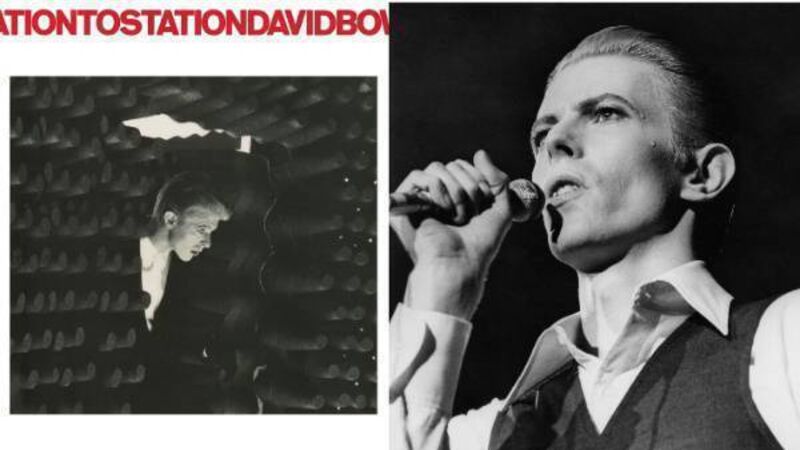

Station To Station, David Bowie: The inside story of the Thin White Duke and the 1976 album

David Bowie released 'Station To Station' in January 1976.

David Bowie’s first American number one single, 'Fame', was a last-minute addition to , his 1975 breakthrough album in the US. It also came with jagged edges and a sneering attitude towards success that even Bowie described as “nasty” and “angry”.

'Fame' gave a first hint of Bowie’s new direction and his controversial character, the Thin White Duke, a persona who would turn the temperature down and invite a much darker, stoic presence.

Scene & Heard

Newsletter

Music, film art, culture, books and more from Munster and beyond.......curated weekly by the Irish Examiner Arts Editor.