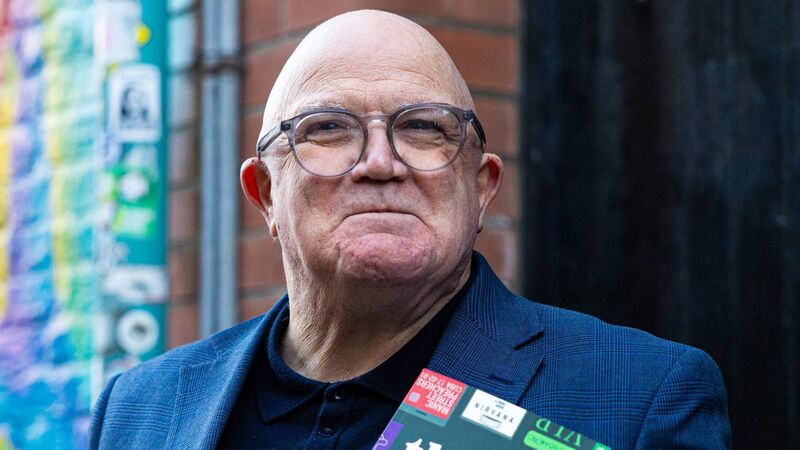

Stuart Bailie: 'The wanker who started Blur versus Oasis'

After serving his time on Belfast fanzines, Stuart Bailie went on to write for some of the top music publications on these islands. Picture: Jonah Gardner

In 2002 Oasis played at Belfast’s Odyssey Arena. As Stuart Bailie stood in the pit taking photographs and jotting down notes he was spotted by Noel Gallagher.

“See that guy down there taking photos?” Noel asked the crowd. “He’s the wanker from who started Blur versus Oasis. Take your camera and f**k off.”