Silent Night: A Christmas ghost story, by Billy O'Callaghan

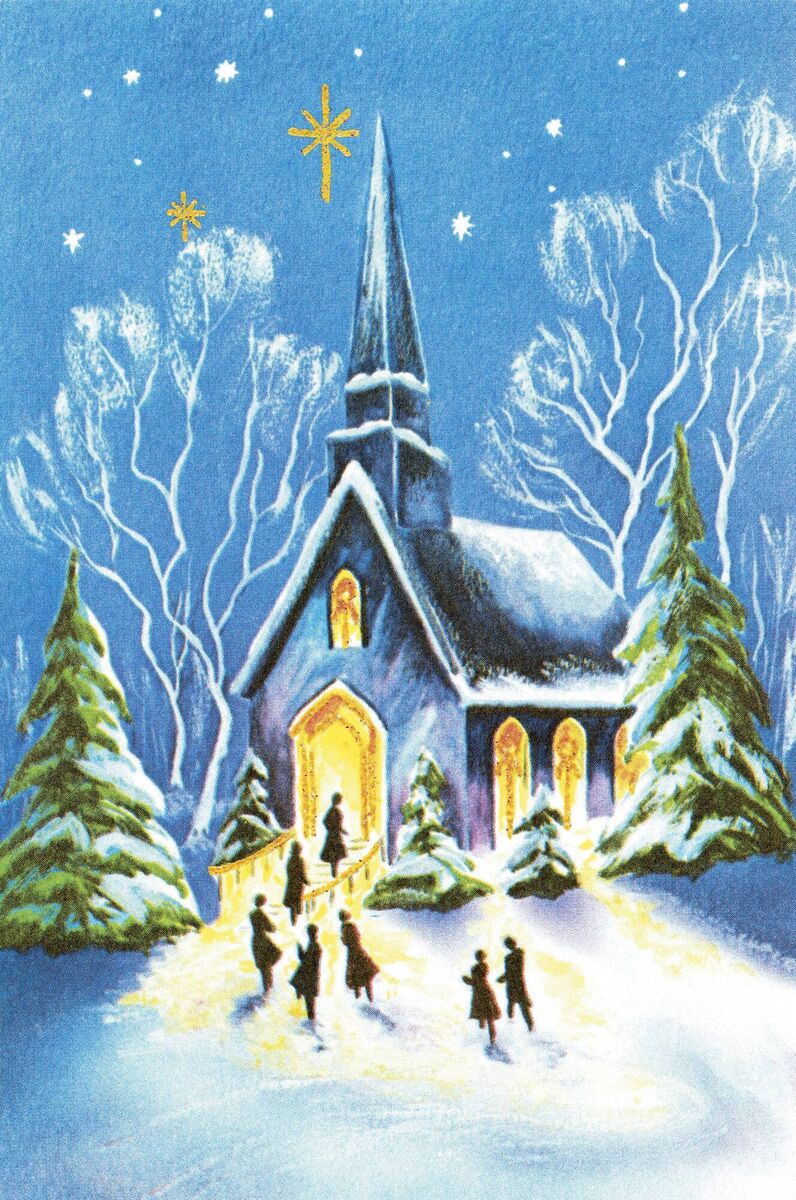

A Midnight Mass, a ruined chapel, and a song that never stops — read Billy O’Callaghan’s haunting Christmas ghost story

A few Christmases ago, a couple of dear friends invited me to join them for Midnight Mass at St. Peter and Paul’s. It was thoughtful of them, since they knew I was on my own, and would, I’m certain, have been a most enjoyable night, a festive supper and good, lively, long-overdue chat at their place, followed by a stroll in through town for the service.

That particular December, Cork had been decked hard and white with frost; the air clean and crisp, the night sky even in around the city brilliantly starlit, and though I’d fallen out of the routine of regular mass-going, the prospect of a prayerful half an hour in beautiful, contemplative, candlelit dark, with the church’s stillness only deepened by gentle carol-song and all around us the most wistful, bittersweet reminders of years’ and people past, should have seemed an idyllic way of welcoming in the Christmas tide. “Not if you lashed me to a horse and dragged me.”

Alice, on the phone, heard my panic as simple harshness and quickly dropped the subject, and after a further minute spent struggling with small-talk found some

excuse, a knock at her door or something, to cut the conversation short.

I sat for a long while then, in dark kept only gently colourful by the twinkling of the lit tree in the corner, feeling chilled to the bone despite how heavily I had banked the fire, with the house around me humming in quiet and all my old ghosts near. And an hour later, I was at Mike and Alice’s door, arriving unannounced, breathless from having had to walk the distance in to High Street from Douglas, clutching a bottle intended as both apology and peace offering.

They, too, had a fire blazing, and while Mike readied drinks for us, Alice stood in tight silence, still clearly on edge with me, in the archway through into the kitchen. But when she saw how my hand trembled in taking the offered glass, and how hard I was fighting to remain together, all her annoyance fell away and, suddenly terribly concerned, she hurried to my side and settled me into the nearest armchair.

They were half my age, still only mid-thirties, and for a couple of years a decade earlier, back when they were first married, had rented the house across the road from mine. They’d been around when Jenny, my wife, was going through her treatment, and even now there’s no measuring the kindness they’d shown us, and the support. I owed them far more than I’d given. At the very least, I owed them some truth.

“I’ve never spoken of this,” I said, once the Jameson had steadied me, “and I’m not sure I should now or that I’ll even be able to. You’ll think I’ve lost the last bit of mind left to me when you hear what I have to tell, about the only other time I ever attended Midnight Mass, but talking of it might help explain the way I reacted earlier, and maybe at last bring me some ease.” I stared at them each in turn, took another taste of whiskey, and began.

In those days, the avenue in from the Passage Road was lined with towering sycamores and horse chestnuts, and with the lateness of the hour, ten minutes to midnight, and except for the crunching of our footsteps on the frozen gravel and our harried breathing in the bitter air, the silence was absolute. Moonlight flashed in stabs through the branches high above our heads, all there was to temper the blackness.

“Are you sure about this, Mam?” Jenny asked, but Hannah just pulled her coat’s lapels together across her chest and strode on, leaving the question unanswered.

Midnight Mass, the thought of it such a good and festive one earlier in the day, but less so now, in this cold and intimidating dark, just out of the village. Jenny’s hand tightened its grip on mine.

She and I wed in ‘73, so this was either the Christmas or two Christmases before that. We’d been doing a line since she was sixteen, and from pretty early on had made up our minds on one another. That year had me working until late into the afternoon of the Christmas Eve – I was still in the mill then, the last few years of the place, before they started laying off – and on finishing my shift, rather than going home, I’d made for her house, to wash away the worst of the oil stench and to eat a bite of dinner, something rough and ready, probably a bit of buttered bread and a few slices of the ham and spiced beef that had been boiled in advance of the following day.

The tree was by the living room window laden with decorations, coloured crepe paper chains stretched in criss-crossing loops from the ceiling, ropes of tinsel decked the mantelpiece and sprigs of fresh-cut vibrantly red-berried holly had been tucked in above every one of the many pictures on the walls. At that time still only in her early fifties but already years’ widowed, Hannah, even with the little she had, loved Christmas.

In the kitchen, because we had a moment with no one else around to see, Jenny drew me into a kiss. “Mam’s idea,” she said, smiling apologetically, though in fact not only did I not really mind, I actually quite liked the thought of it. “You know how she is, once she gets a notion.” I ate the meat Jenny had sliced for me, and after hurrying up the hill to home for a more thorough wash and a clean set of clothes, was back in good time for the three of us to walk the half-mile together, down past the Finger Post to Windsor, with the air skinning, the paths treacherous in places, and frost thick as fur on the ground.

The trees broke onto a clearing ahead of a large squat building, its grey front shining like bone in the moonlight, a place that seemed deserted at first, abandoned, until we noticed light, not in the windows but seeping through as a kind of softness, almost more felt than seen, from somewhere deeper within. Jenny beat a few times with the iron knocker on the front door, the hard sharp noise of it in the nighttime quiet like shots being fired.

For a full minute nothing changed within the stillness, until movement sounded within, footsteps laid down quietly on a tiled or flagstone floor, and then the door opened and a man dressed in black, a priest, tall and blonde and very thin, young and yet at the same time, in the moonlight, oddly old-seeming, loomed at the threshold.

“We’re here for Mass, Father.” I had to clear my throat to speak, and again Jenny’s hand squeezed mine.

The priest studied us. “I’m sorry,” he said, his tone distracted, as if he’d been interrupted and was still, part of him, among his prayers.

I tried again, assuming some confusion. “It’s just that we heard there’s to be a midnight service.”

“There is,” he said, in the same vague manner. “But tonight’s Mass is private.”

“What are you talking about?” Jenny’s mother pushed past Jenny and came to the bottom of the steps. The priest loomed above her. “My uncle Mickey was waked in the chapel here,” she said, in that unflinching way I’d already come to recognise. “My mother was born on this doorstep, nearly. How can Mass be private? Sure, isn’t Christ for everyone?”

“I’m sorry,” the priest said again, in that tone of merely thinking aloud, and remembering the slow way he lifted his gaze from her, and raised it, as if there was something more than stars to see above us, still for reasons beyond my understanding causes me to shudder. “The service is for the seminarians only. Now, it’s late, and I’m afraid you’ll have to leave.” Then, abruptly, without the glad tidings of the season or even so much as a good night, he took a step back into the dark of the hallway again and swung the door shut on us.

That should have been an end to it. We stood a few moments longer in that moonlit driveway, perished and not a little unsettled but, speaking for myself, anyway, also quite relieved, and then Jenny, squinting at the watch on her wrist, announced, high with affected happiness, that it was officially Christmas. “Already gone

midnight,” she said, contemplating I’m sure the idea of a roaring fire and a glass of something that would warm the cockles. “Come on. Let’s get home, in out of this cold.”

We turned to go, but Hannah, ignoring all that had been said, set off in a different direction, along the channel between the treeline and the front of the building and then around its far side, into the blackest dark. “Mam?” Jenny called after her, trying to keep her voice to a hush even as it betrayed an urgency, and when that met with no response, hurried to follow, leaving me with no real choice but to follow, too.

“The chapel must be back here,” Hannah said, once I’d caught up. “Don’t worry. We can stand in the porch, or tuck in where we won’t be seen. It’ll be grand. No one will pay us any mind.” This side of the house had the moon fully eclipsed, turning the night impenetrable, and with the air, sheltered from the least movement of breeze, scorching the flesh of our faces, instinct slowed our advance and had us holding on to one another for reassurance.

And then, faintly, so soft at first as to be almost nothing, we caught the murmur of singing, a kind of carol but one I couldn’t have identified, Latin, I suppose, or some archaic form of Irish, a low, heavy drone with little to it in terms of melody, and lifting only a little in volume as we drew nearer. But if the strangeness intimidated me, it only served to buoy my future mother in-law. “They’ve started,” she said, breaking from us and quickening her step, forcing Jenny and I into a kind of half-run to keep pace, though the dark remained unyielding and the sound, what there was of it, seemed to come from every direction at once, seeping from the walls and up out of the ground and from the very air around us.

There was a building set back behind the main house, its details kept cloaked in darkness except for a tallow glow, candles or lanterns, filtering only barely through small corroded windows set high above our heads the length of its flank, and the singing abated a moment then started up again in a beautiful if unsettling rendition of what had at least the timbre of Silent Night, a singular voice in lilting baritone until the choir rejoined in something of the same almost chanting drone as before.

We tried the first door and found it shut, and instead of struggling with it we hurried to a second, further along, this one, of thick oak and iron bands, standing already a few inches ajar. Even so, Jenny couldn’t budge it, and it took all I had to drag it open even just enough for us to be able to squeeze through. The instant we did, spilling into a narrow stone alcove to the right of the altar, facing a small, dim, clearly ancient chapel and its tightly-bunched congregation, everything fell to dead and sudden silence. At first I assumed it was due to our interruption and I started to raise a hand in apology, but then, all at once, I saw.

Jenny pressed herself hard against my side and, half a step ahead of her, Hannah, who I’d never known to fear anything, took a fistful of my coat-sleeve and gave the tiniest gasp, something close to a whimper.

Before us, the pews were packed, not with priests but by men in habits, dark gowns of the crudest, most basic kind, the entire congregation in the throes of either prayer or song and oblivious of our presence, and even in the lantern-lit dimness I could make out the expression identical on each and every face, stretched with ecstasy and fervour, eyes either clenched shut or wide in fixation, mouths agog in fullest-throated roaring. And yet all was silent. There’s no explanation. It was like watching television with the volume turned down to nothing.

I was the first to stir, though not for a minute, or maybe even longer, transfixed as I was, as we all were. Spellbound, maybe. “Move!” I whispered, and pushed the women back towards the door still mercifully standing that stuck foot or so ajar behind us. That was the worst moment, actually, having to wait for them each in turn to squeeze though what was essentially a crevice, and wanting nothing more than to run and never stop, and then as Hannah struggled into the narrow space, with Jenny, already outside, and sobbing now, dragging her by one arm, I made the terrible mistake of looking back. I couldn’t help myself. And at that exact moment, still in the crushing silence, every face in every pew turned from its soundless singing. And I was the one who screamed.

Outside, the night was as before, the same intense darkness, the cold as searing. Hannah had succeeded in grabbing hold of me, and I suppose, sensing freedom and overwhelmed by desperation, I’d managed to press myself through the gap. The instant I was clear the singing again surrounded us, as if the dark had once more regained its measured volume, the mid-carol continuance of the interrupted Silent Night, except now the sound, Latin or whatever it was, some grim many-voiced canticle, had our skin violently crawling.

Pushing and dragging and holding tight to one another, we ran, carrying the terrible, chilling sound of that singing with us, losing ourselves – and our minds, too, nearly – a minute among the trees before reaching the road again.

At first, no one spoke. “That’s some story,” Mike whispered, finally, and when he stood to refill our glasses I couldn’t but notice how his hands were trembling now, too, and also, seated still across from me, how distant Alice’s gaze had become.

Even between ourselves, I explained, because more felt needed, even in the years after Jenny and I were married, we never discussed what we’d seen. But it hadn’t gone away, and I used to see sometimes the worry of it in her eyes, and knew – because it continued to happen to me, too, and still does, even now – that she’d caught a strain of that awful singing again in the silence. “At home,” I said, “especially at Christmas, we always had music playing, or a radio or television on. Something, anything, to fill the void. And it’s been mostly enough.”

After this, Alice made sandwiches and a pot of tea, cut slices of the cake she’d baked and iced herself, the way her mother had shown her, years back. There were other things to talk about, our plans for the coming week, things that still needed doing, last-minute shopping, cutting holly for the pictures at home and to decorate a wreath I’d made for Jenny’s grave, but all of that felt half-hearted now, colour for the surface.

When the time came to leave, I shook Mike’s hand, kissed Alice’s cheek, wished them the happiest of Christmases and, in acknowledgement of their repeated offer, which they insisted would remain open, Alice suggesting that Midnight Mass might actually be just what I needed, I nodded, pulled on a smile and said that, all right, I’d give the matter serious consideration. Outside the night was dark and bitterly cold, and the stars were shining. I walked the hundred yards to the nearest bus stop, and saw no more than half a dozen cars and no pedestrians at all during the ten minutes I had to wait. And silence reigned.

What I hadn’t said, and couldn’t, not that night, was that I’d gone back. A couple of years after. Not at night, of course, or at Christmas, but alone, telling no one. An evening in midsummer, one of those that hold on long to their glorious golden light, with the air sweet and tranquil, swimming in birdsong. Two years had changed nothing of the place, not the way half a century has, with the seminary a hotel now and long since, the avenue in from the road still then as it had been, and the house much as I’d previously seen it, and once I got close enough I could hear the murmured talk of young priests in the fields behind the house, easy at work among the vegetables.

Along the path we’d previously followed, and around the far side of the building, the light made what I’d remembered seem imagined or at least exaggerated, yet there was still something disquieting on that side, a heft to the silence that didn’t feel right, or natural. And then, again, suddenly, there it was. A ruin: a few eroded stumps of walls, roof and roof beams lost to rot or reclamation, holes where windows had been, the innards, from what I could make out of them, long since torn away.

Whatever had gone on here hadn’t happened overnight; this was clearly centuries of collapse. It was the same spot, I felt certain of that, but I wouldn’t otherwise have recognised it as a chapel except that, further along towards its end, a door, of ancient oak and wide iron bands, stood largely undamaged, a foot or so ajar from its stone archway. And in the gap, the sliver of space, shadowy because of the evening’s brightness, something seemed to be moving. This time I didn’t scream, but I did turn and run, knowing better than to risk a backward glance.

Christmas, for all its merriment and hectic bustle, can’t help but keep its ghosts near and, in those long silent nights, for the lonely and the haunted, singing. And that’s how it’ll continue to be, until the end.