Books of the year: 2025’s best offerings that highlight political strife, pain, and injustice

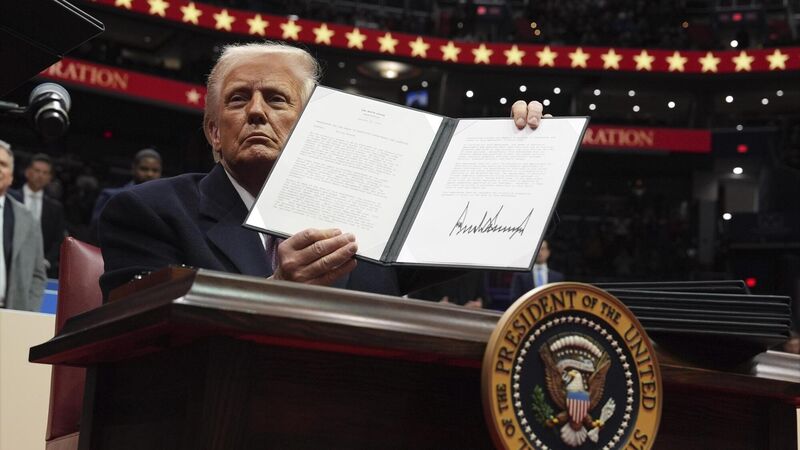

Donald Trump declared ‘a national emergency at our southern border’ at his inauguration in January. File picture: Evan Vucci/ AP

The third Monday of January is officially the most depressing day of the year. It was fitting that Donald Trump’s inauguration fell on Blue Monday 2025.

The pleasantries inside the US Capitol rotunda in Washington DC didn’t last long.

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.