The Thing With Feathers: Benedict Cumberbatch on grief and his Max Porter adaptation

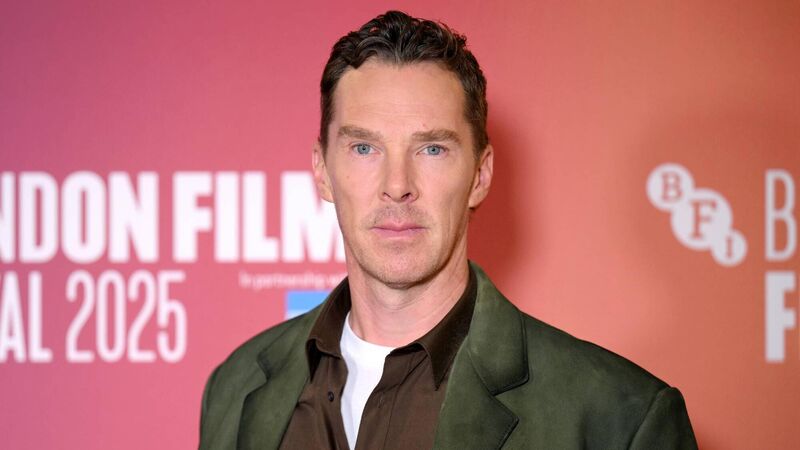

Benedict Cumberbatch at a screening of The Thing With Feathers, on general release this week. Picture: Kate Green/Getty.

If we were told when we would die, Benedict Cumberbatch doesn’t think it would better prepare us for the finality death brings. The 49-year-old BAFTA and Emmy Award-winning British actor, who stars as the grieving Dad in Dylan Southern’s adaptation of Max Porter’s book believes our brains can sometimes protect us from dwelling on our inevitable demise.

“Nothing really prepares you for that sense and reality of loss. You can breed an acceptance of impermanence, whether it’s through philosophy or meditation, but you can’t really know what it’s going to feel like when you reach that end date,” says Cumberbatch, who played Sherlock Holmes in the mystery crime drama Sherlock.

– British filmmaker Dylan Southern’s debut feature – follows a widowed father, simply called Dad, who suddenly loses his wife and is left to raise their two young boys, played by Richard and Henry Boxall.

As his life begins to unravel, Dad’s grief takes the form of an unhinged and unwanted house guest, Crow, portrayed by star Eric Lampaert, 39, but voiced by 62-year-old Harry Potter star David Thewlis. As Crow continues to taunt him from the shadows, things start to spiral out of control for Dad.

Cumberbatch adds: “Max’s novel is an exceptional piece of prose. It’s lyrical, damaged, salvational, majestical, mundane, domestic, real and surreal. It is an extraordinary prism through which to reflect grief – the structure and intimacy of it.

“When reading it, I had the most amazing film playing in my head. The nature of the source material challenges you into imagining it, how it touches on something deeply personal.

“It’s difficult to adapt a book that is so complete in so many ways. You want to do something different with it, but you don’t want to completely deconstruct the DNA of it.

“I wanted to keep Dad’s humanity. I wanted, as an actor, to be able to bring across somebody who is very human in his failings – someone who is working through things moment by moment.

“I think everyone in the film, from [author] Max through to us, knows that grief is a universal experience. It’s also a very rare thing in culture to explore that through a male experience,” says Cumberbatch of a role played by Cillian Murphy in the stage adaptation.

When Southern – best known for his indie rock documentary film – was a teenager, he lost his best friend and another friend in the same year.

“These deaths left me bewildered. I’m sure things have gotten better now, but at that point, as a young man, I had never been provided with the tools to deal with the overwhelming enormity of that kind of loss. I tucked it away. I carried it with me. I unknowingly allowed it to grow,” says Southern, who is also directing the upcoming Oasis tour documentary,

“Reading Max Porter’s novella years later was one of the most cathartic experiences of my life. It gave me an insight into feelings that men (and perhaps particularly British men of a certain age!) don’t get taught to deal with. It gave me the language to discuss how unsubtle, messy, chaotic and persistent grief can be.

“Importantly, it did so in a way that was masterfully laced with the same brand of absurdism, gallows humour and honesty, the same avoidance of sentimentality with which I approached my own experience of loss.

“The book is unapologetically unsentimental about death and loss; it is abrasive, tender, violent, soft… it’s genuinely funny, kind, not to mention ridiculous in places. I was astounded by the way those disparate tones combined to allow access to genuine human truths in a way I hadn’t experienced before.” So when it came to adapting the 44-year-old English writer’s book, Southern was keen to structure the film in a way that “maintained its DNA” but was more “palatable for people watching in a cinema”.

“Max’s novel is structured in three separate sections, very different to what we have done with ” says Southern. “He does things that you can’t do in a film. For example, the book is told from three perspectives, but sometimes the tense is different.”

“It often feels like the boys are adults looking back at their childhood. Dad feels very anchored to the present, and Crow is just this unreliable narrator who kind of comes in and messes everything up. I could have jumped all over the place like he does, which you can in a book, but people would have found it quite hard to follow. But I think for me, that the first section is the raw horror of grief, which is why the film leans into some tropes of horror.

“It was never going to develop into a full horror film, but I wanted to convey the beginning stages of grief, the shock, the not knowing what’s next. Even though the worst has happened, you feel like there’s worse to come, and in some ways there is. I think when we get into Crow’s section, it is the arrival of that unreliable narrator. Grief isn’t something that you move through in five stages and then it’s over."

Southern says each one of those stages is reflective of something that happens in grief. "But it’s like they’re in a washing machine, and jumbled up, and they might come back in 10 years’ time and hit you just as hard as they did the first time.”

Cumberbatch thinks it’s really important to emphasise the pressures that come with navigating the different stages of grief. “This idea that there are stepping stones [in grief], will make you think that you’re some kind of awful fu**-up if you don’t experience things in a consequential order,” adds Cumberbatch.

“And you’re not, you’re a human being, and you regress, make the same mistakes again, have the same feelings again. You don’t just move on. Grief is with you for life, and it comes back so unexpectedly, almost as heavily as the funeral, or whatever moment it is where you first fully feel your loss.”

Southern agrees and adds: “Someone who has experienced that kind of thing versus someone who fortunately hasn’t, has a different relationship to life and other people, and not better, not worse, but richer and more guided by their experience.”

- comes to cinemas on Friday, November 21