Animation in Ireland: ‘It goes back to the Book of Kells’

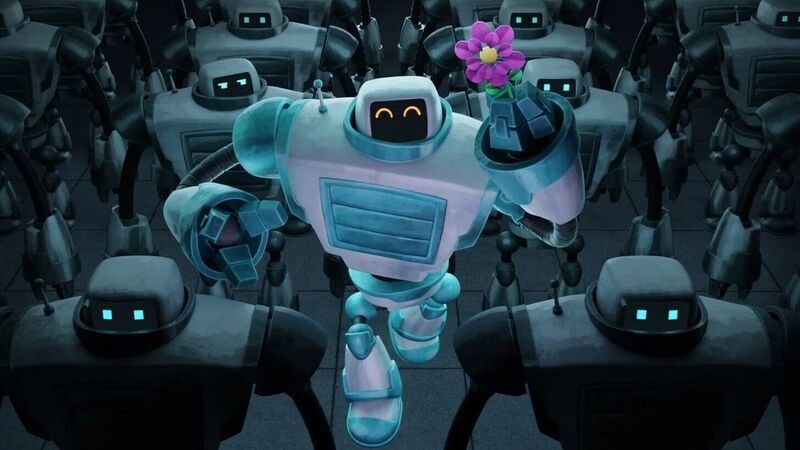

Will Sliney's Droid Academy, a new RTÉ-commissioned short

In middle of the last century, a time existed when Disney was the only studio in the English-speaking world that regularly produced feature-length animated films. It didn’t last long.

“American drawn-animation feature films died a death around the 1980s when they became too expensive to make,” says filmmaker and animator Steve Woods, whose book covers the long story of Irish animation.