Pablo Picasso: Irish exhibition features key works from the Malaga marvel's career

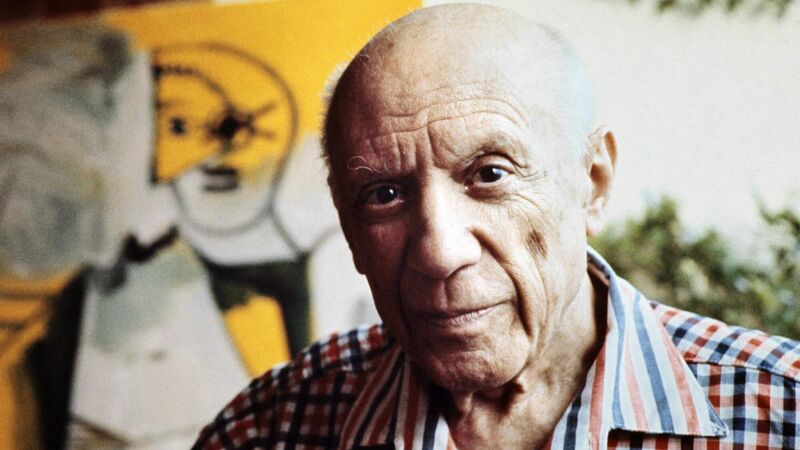

Pablo Picasso produced tens of thousands of artworks before his death in 1973, aged 91. (Photo by Raph GATTI / AFP)

Pablo Picasso famously described his art making as “just another way of keeping a diary". Born in Málaga, in southern Spain, in 1881, he moved to France at nineteen, working in a succession of studios that began as bare attic rooms in Paris and evolved into ever grander spaces as he became more and more successful. In each, he recorded the experiences of his colourful – and sometimes tumultuous – life, in a great outpouring of paintings, prints, drawings, sculptures and ceramics.

Picasso could be accused of many things, but idleness was not one of them; on his passing, aged 91, at his private Mas Notre-Dame de Vie estate in Mougins, it was discovered that he had 45,000 unsold artworks in his studios. He left no will, and his descendants settled his death duties by donating a large body of this work to the state, much of which is now housed at the Musée Picasso in Paris.