Book review: Extensive portrait of a Prince of music invites questions

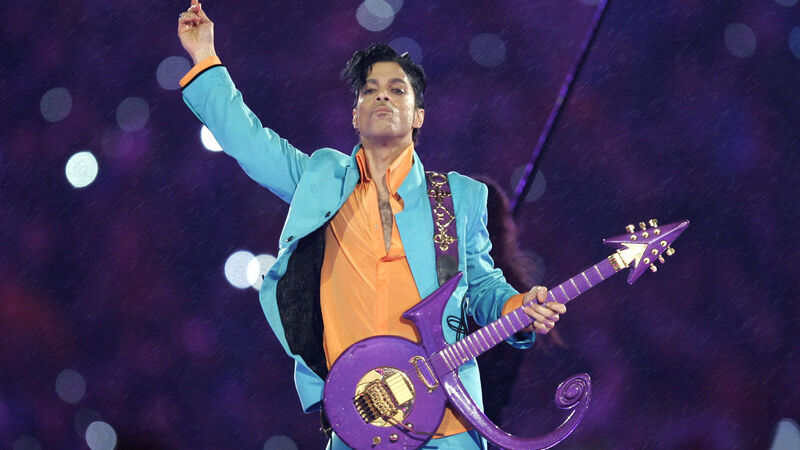

Prince performing at the halftime show at Super Bowl XLI in 2007 at Dolphin Stadium in Miami. Prince believed it was vital to look good to play good. File photo: AP/Chris O'Meara

- Prince: A Sign o’ the Times

- John McKie [Blink]

- Review: Colm O’Callaghan

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.