Karl Whitney: Is it better to let ideas fumble on the long route or set them in stone?

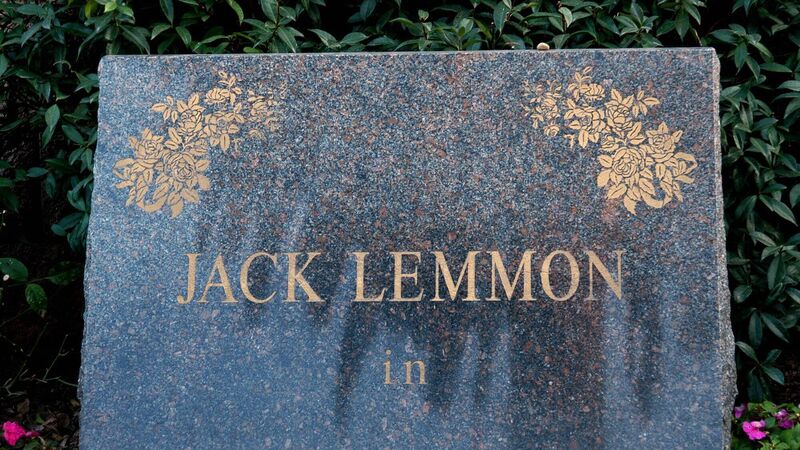

The great comic actor Jack Lemmon’s gravestone reads: ‘Jack Lemmon in’; there's nothing like a gravestone to limit the word count. Picture: Barry King/WireImage

I was walking around a graveyard the other day — a good place to think about writing, particularly concision.

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.