Book review: Memoir rich in literary allusion, social mobility, and so much more

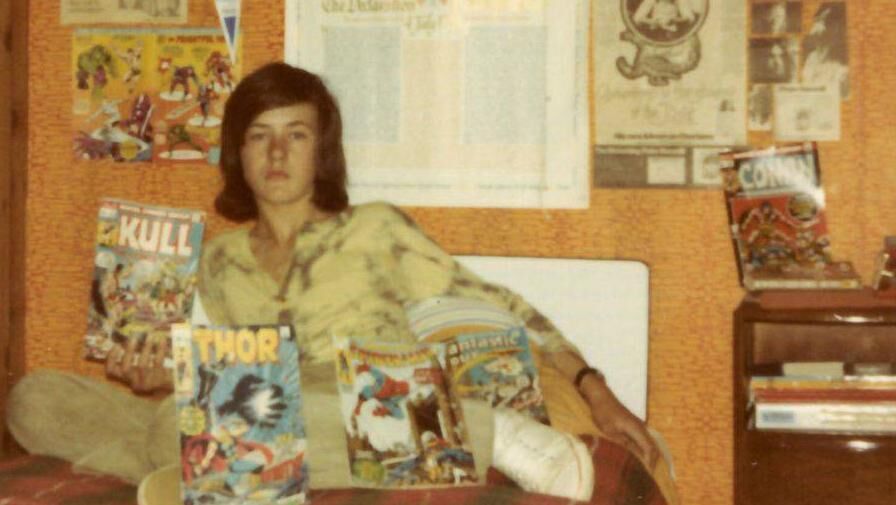

Geoff Dyer’s 1960s working-class childhood is depicted as unapologetically ordinary, filled with the boyish toys and past times that arouse gentle nostalgia for the mid-20th-century world.

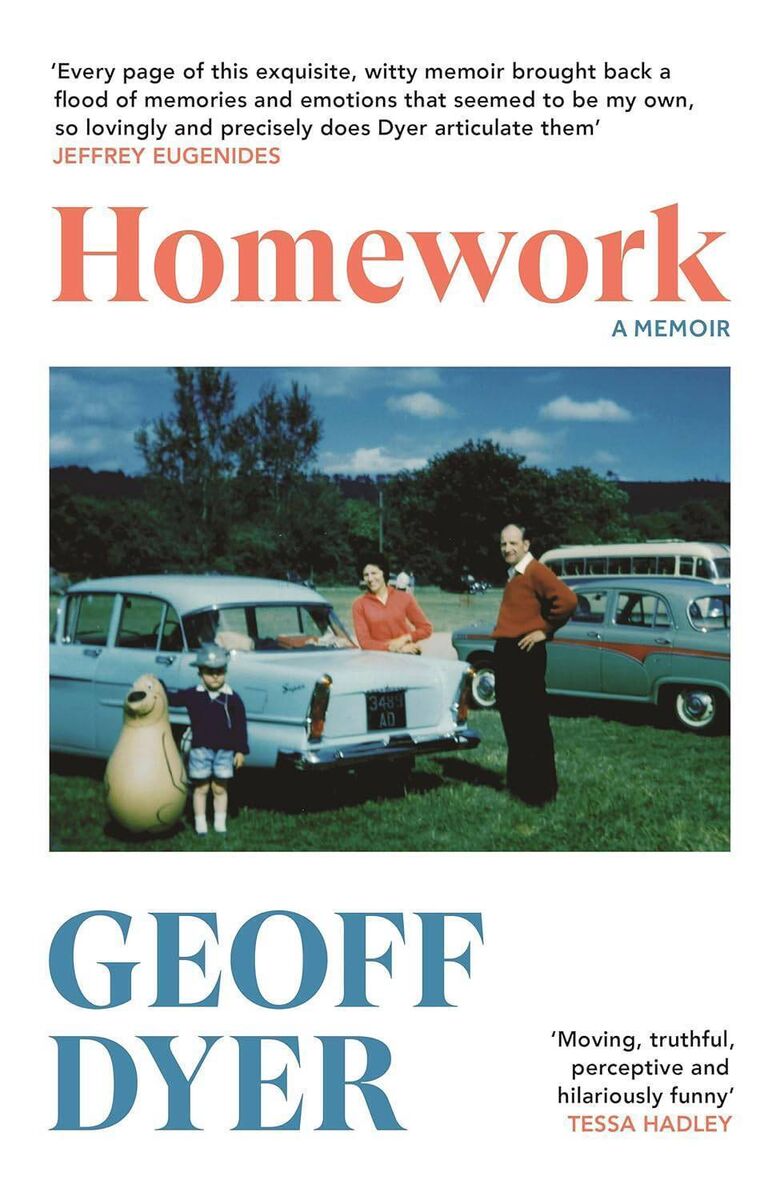

- Homework

- Geoff Dyer

- Canongate, €20.99

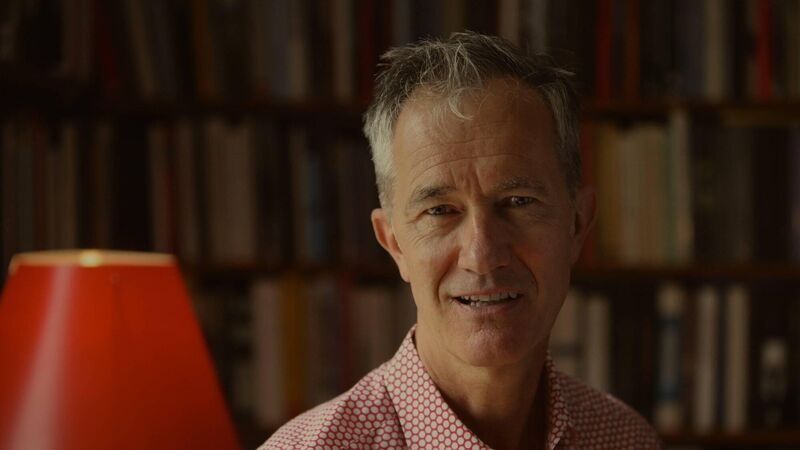

It has become commonplace to laud English writer Geoff Dyer for his versatility, but that makes the praise no less valid.

A multi-awarding author of numerous works of fiction, non-fiction, criticism, and other surprisingly genre-defying books, he has now turned his highly accomplished hand to memoir.

is an account of Dyer’s upbringing in Cheltenham in the 1960s and ‘70s, a world he evokes in gloriously minute, Proustian detail.

But, naturally, the two central people in his life — and in the book — are his parents.

Dyer’s family history also acts as an account of social mobility in England over a century or so.

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.