Book review: Keeping tabs on propaganda

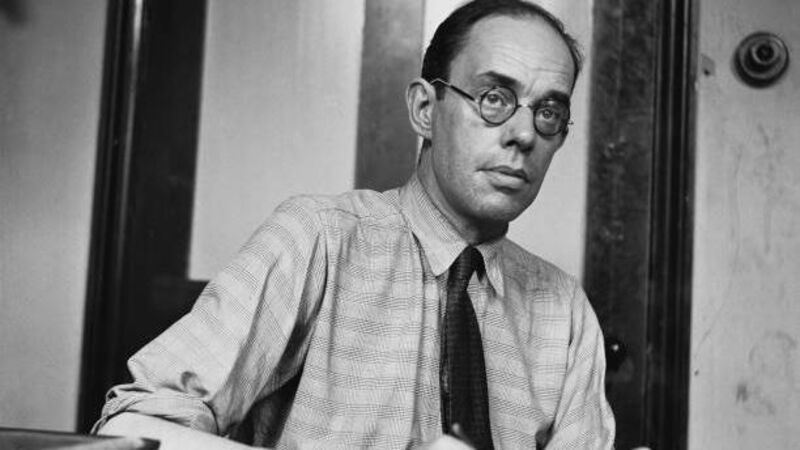

Claud Cockburn edits 'The Week', the magazine he founded in 1932; an anti-establishment, anti-Nazi voice, the magazine challenged conventional wisdom when doing so was dangerous.

- Believe Nothing Until It Is Officially Denied: Claud Cockburn and the Invention of Guerrilla Journalism

- Patrick Cockburn

- Verso, hb €35.00

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.