Books of the year: Worlds of fantasy and fame brought home to the local

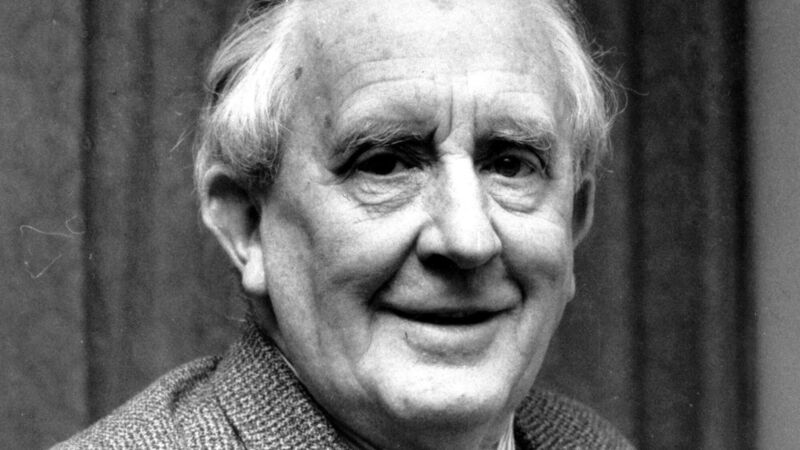

JRR Tolkien: The Ring encapsulates and exposes one of our defining delusions of power and how we would use it. Picture: AP

I was a late convert to JRR Tolkien. At the very time in my life, male adolescence, when (at least, as far as the stereotype goes) I should have been most susceptible to him, I was, in fact, completely indifferent, greeting any reference to or with a shrug. I wasn’t hostile but I had no interest in him or the fantasy genre.

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.