'She wanted these children remembered': The story behind the new sculpture in Innishannon

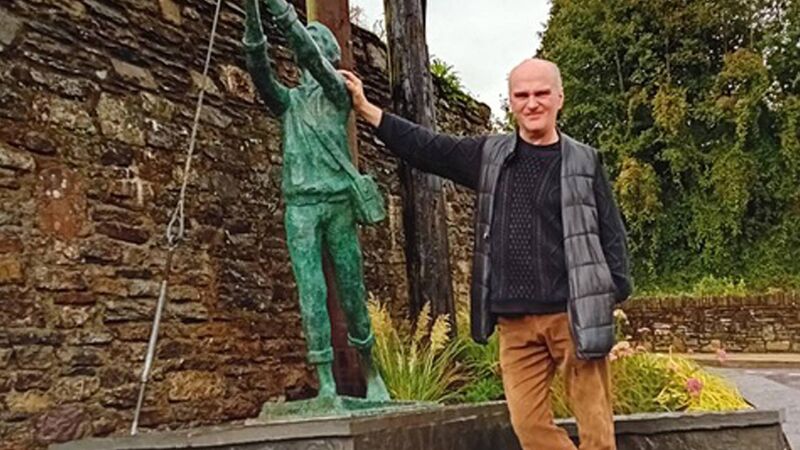

Sean McCarthy in Innishannon with his new sculpture. Picture: Denis Boyle

The unveiling of Seán McCarthy’s Charter School Boy in Innishannon, Co Cork on Sunday 13th October marked the completion of a local initiative to commemorate local history through a trilogy of public sculptures. McCarthy’s work joins two other bronze sculptures in the village; Billy the Blacksmith at the west end, and the Horse and Rider at the east.

McCarthy’s sculpture, which depicts a schoolboy releasing a bird into the air, occupies a site outside the Old Rectory in the middle of the village. The site was chosen because a Charter School once stood behind the Rectory, on a two-acre site donated by the local landlord Thomas Adderly. Established in 1752, the Innishannon Charter School was one of fifty such institutions around the country that provided training for boys and girls so they could secure work in the linen industry.