Book review: The sordid and confused spy world of an unfaithful vassal in sixties Britain

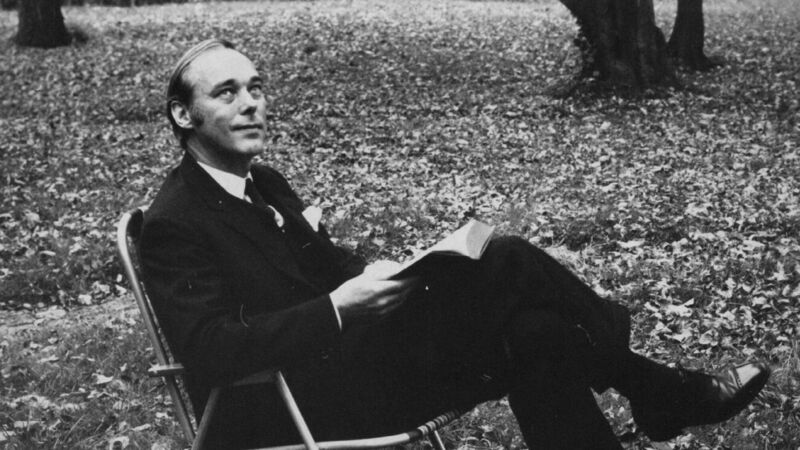

John Vassall spent a decade in jail for spying unable to understand why so many others got away. File picture: Evening Standard/Getty Images

- Sex, Spies and Scandal: The John Vassall Affair

- Alex Grant

- Biteback Publishing, €25.00

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.