Book review: Intriguing essays revive spirit

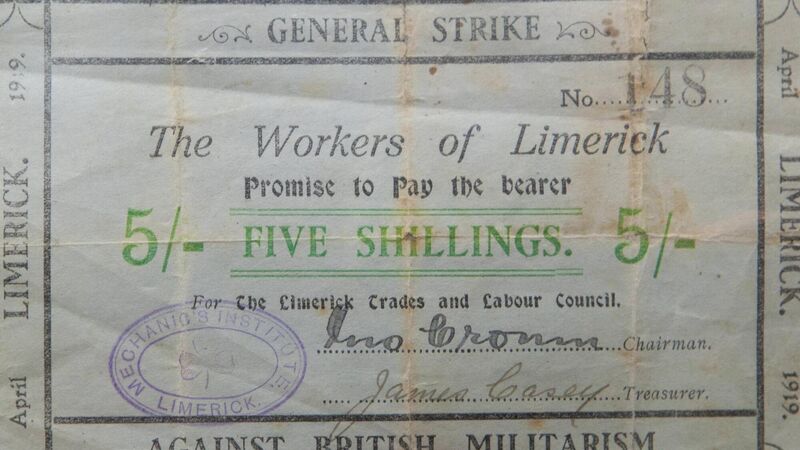

Extremely rare Limerick Soviet five shillings note inscribed 'April Limerick 1919 — General Strike Against British Militarism'. File pictur: Brian Gavin/ Press 22

- Spirit of Revolution: Ireland from below, 1917-23

- Edited by John Cunningham and Terry Dunne

- Four Courts Press, pb €22.45

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.