Book review: The Letters of JRR Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition

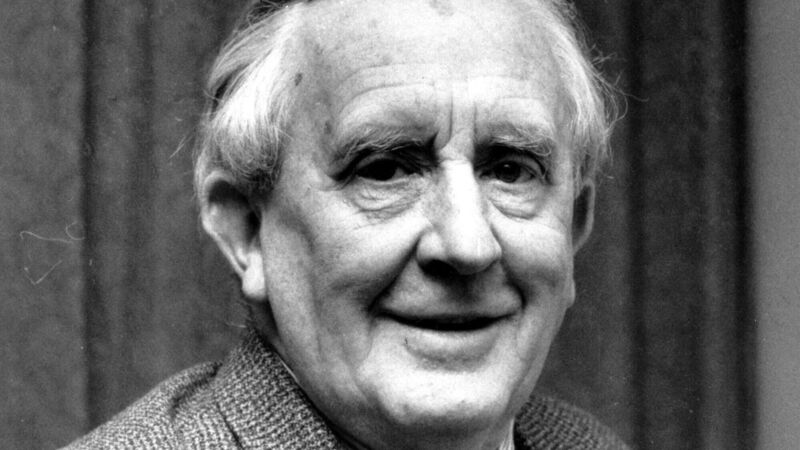

JRR Tolkien in 1967: His politics tended towards a certain kind of anarchism and he abhorred racial stereotyping. Picture: AP/File

- The Letters of JRR Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition

- Edited by Humphrey Carpenter with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien

- Harper Collins, £30.00