State support for Irish authors is ‘transformative’

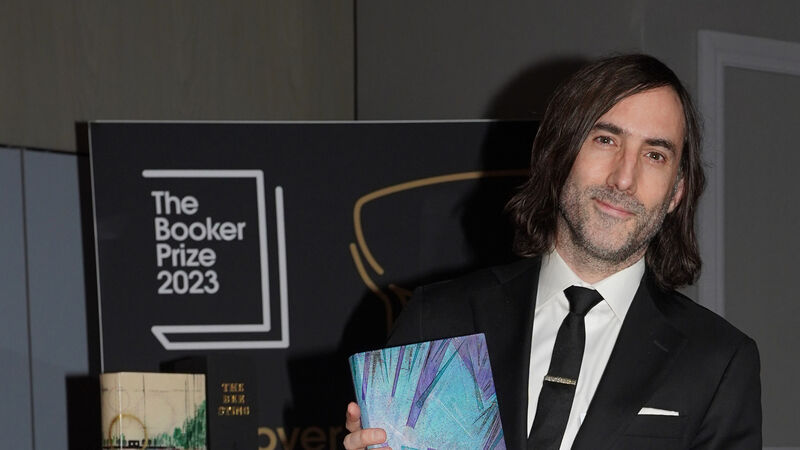

Winner of the 2023 Booker Prize Paul Lynch for the novel 'Prophet Song', at an award ceremony in Old Billingsgate, London, last month.

When Paul Lynch won the 2023 Booker Prize last week for his novel , it marked the sixth time an Irish author has won the prestigious literary award.

This year, there were four Irish authors on the longlist of 13. That meant that Ireland has now produced the most nominees, relative to population, in the prize’s history.