Book Review: Aoife Moore's look into Sinn Féin is courageous but incomplete

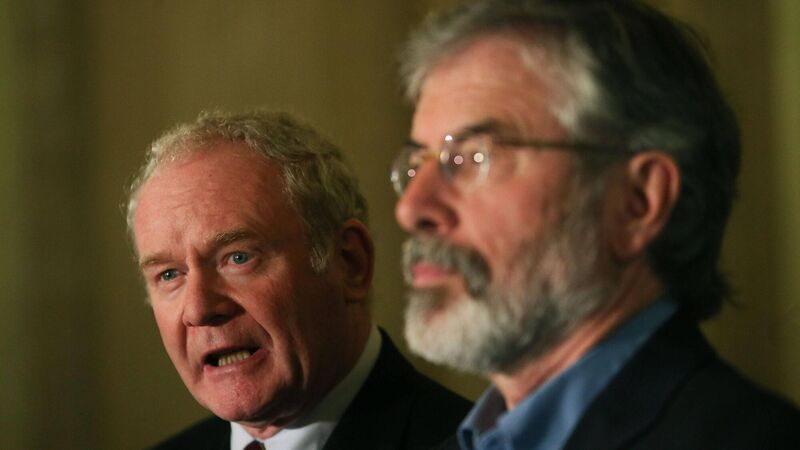

One genuine revelation in the book is that Martin McGuinness wanted Adams to temporarily step aside as Sinn Féin leader in 2013 when his brother was convicted of the rape of his daughter over a six-year period. Picture: Brian Lawless/PA

- The Long Game: Inside Sinn Féin

- Aoife Moore

- Sandycove, €17.99