Claire McGowan: Disability isn't an easy narrative - it's a spectrum

Claire McGowan Picture: Donna Ford

Profound disability is not a favoured subject of novels, especially when the main female character abandons her disabled child.

Meet Kate, mother of profoundly disabled Kirsty and profoundly ignored Adam.

Kate used to have a job in television — she was a natural — until she sleepwalked into marriage and motherhood with the profoundly dutiful Andrew.

Kate is not a natural mother; she is neither mumsy nor self-sacrificing.

When Kirsty, whose disability is so rare it doesn’t have a name, comes along, life unravels.

Five years of miserable family life later, Kate can’t do it anymore.

She disappears without any further contact, leaving both children behind, plus everyone else in her life.

Her friend Olivia, co-dependent and people-pleasey, steps in to help Andrew and the family unit survive.

Kate starts again in LA, partnering with Conor, a successful, emotionally-cauterised man who is a film producer in Hollywood.

What should have been the end of it — Kate’s decision, while monstrous, is also honest and understandable — is disrupted when, years later, her ex-husband Andrew writes a book about how he learned to communicate with Kirsty using special sign language.

How it transformed his relationship with his disabled daughter. The book becomes a best seller. And guess who options the film rights of the memoir of Kate’s first husband? Yup. Kate’s second husband. Reckonings ensue.

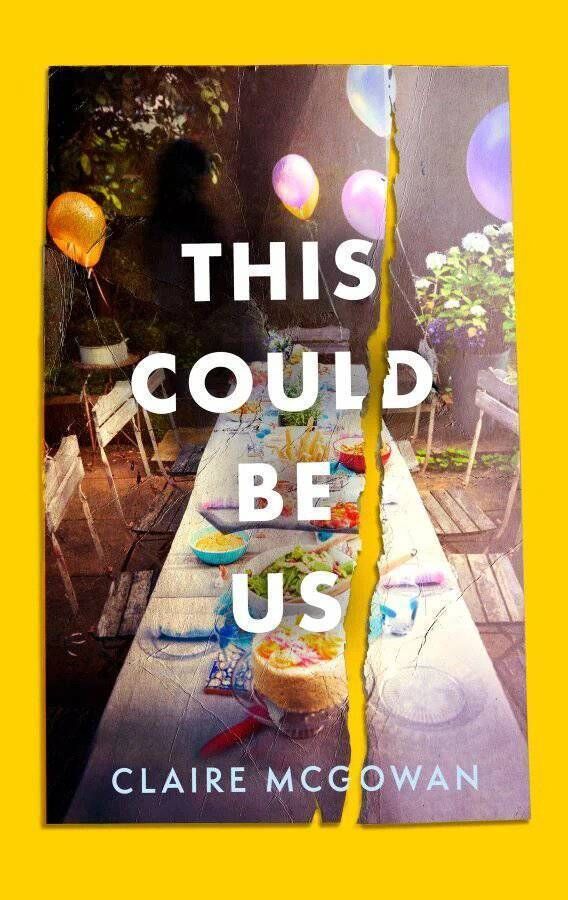

This is the plot, which flits backwards and forwards over a 20-year span, of Claire McGowan’s latest novel, This Could Be Us. It’s a page turner.

McGowan, born in Northern Ireland in 1981 and now living in London, knows how to plot a story; since the publication of her first novel in 2012, she has published over 20 crime novels, plus women’s fiction titles under the name Eva Woods, as well as writing for radio and TV. She also spent five years teaching an MA in crime writing.

This Could Be Us, she tells me, has had the longest gestation of all her books. “It’s been a long time in the works,” she says.

“I started writing it in 2011, but I put it to one side because I didn’t feel like I had the skills to tackle it at that point. In lockdown, I got it out.”

McGowan knows all about growing up with a profoundly disabled sibling. She was two years old when her younger brother was born with a chromosomal disorder so rare it doesn’t have a name; he cannot communicate, or look after himself.

He was — and is — cared for at home, full-time, by her parents. Growing up in rural 1980s Ireland, the lives of McGowan and her siblings were deeply impacted by the severity of her brother’s disability.

The family received little outside support, practical or otherwise. “All through childhood both my parents worked full time, and sometimes in the evenings as well,” she says.

“There was a lot going on, all the time. My brother used to have a lot of epileptic seizures which were frightening — we often thought he was going to die.”

In her author’s note at the beginning of This Could Be Us, she writes about how we have a tendency to categorise ‘disability’ as a single thing, whereas in reality it’s a vast spectrum, from Northern Irish Oscar-winning actor James Martin, who has Down’s syndrome, to someone like McGowan’s brother who has little awareness of his surroundings and whose adult needs are that of a small baby.

And how past attitudes towards disability were primitive, to say the least.

“Often adults would just stare at us, which would make us feel terrible, as though there was something wrong with us as a family,” she remembers.

“My brother used to shout quite a bit — he still does — so people would stare. In more recent times there’s been a shift towards being more positive about disability, which is great and much more inclusive, but it still neglects what we’ve experienced. Someone so profoundly disabled they don’t know where they are or what’s happening, that you can’t really have a relationship with. It’s hard to find any positive in that situation. The Catholic Church would always try and tell us there were positives, which I used to find really annoying. ‘You’re family’s so lucky, you’re so blessed’, and we would be really struggling.”

She suggests this pressure on the families of profoundly disabled people “to be positive all the time” was due to Ireland’s abortion ban.

In the novel, she explores the idea of what it means to carry ‘faulty’ genes.

McGowan doesn’t have children herself, but this is not because she is a carrier of the chromosomal disorder. “Typically with these kinds of conditions, you either have it or you’re a carrier,” she explains.

“I was tested when my brother was born, so I have always known that I don’t carry it. “Very understandably, disability campaigners are concerned about the narrative that you should always end a pregnancy if there’s a disability, but it’s really hard to speak about disability being one thing.

Someone with Down’s syndrome can have a pretty amazing life, which is so different from my brother’s experience.

I find it hard to explain just how different, and sometimes people think I’m being unkind, but it’s the truth. I don’t even think my brother knows who we are. And people don’t want to hear that.

The disability in the book, that the Kirsty character has, is much less severe than my brother’s. I’ve sugar-coated it.”

She adds how her family “didn’t get any counselling or any support, despite such a traumatic situation going on. Nobody even suggested it. Now, children with a very disabled sibling have their own social worker.”

What, then, would she advocate for profoundly disabled people and their families, if she were in charge? “So much more support is needed,” she says.

“People have no idea how difficult it is — it’s like having a newborn baby that’s going to be like a newborn baby forever. Often in private care places, the standards of care are not very good — my parents are concerned that if they put my brother in long-term care, he wouldn’t survive. He needs dedicated care. That’s your choice — care for someone until you drop, or put them somewhere they may not survive. It’s pretty stark. So we need much more daycare. The existing support that is there needs to be massively increased and regulated and made better. And I think it would be good to have mental health support from the start. It would have been great if we’d had some as kids, if there’d been someone to say, ‘it’s ok to feel upset or overlooked yourself’.

“Being told to feel grateful is really terrible, but that’s all we got from the church, with no practical help whatsoever. It was really difficult. And the situation continues to be not that great. We need to acknowledge that while many people with disabilities have amazing lives, this is not the case for everyone.”

I ask how her brother is doing now, in adulthood. “He’s in quite good health,” she says. “We don’t know what his life expectancy is, because he wasn’t expected to live much beyond birth. He’s going to be 40 this year, and still needs ‘round the clock care, still lives at home with my parents.”

Which is what makes the Kate character in McGowan’s novel so transgressive — the fact that she bails.

Unlike fathers, it is taboo for mothers to ever leave the family; to abandon a disabled child doubly so. “There’s a stigma around leaving,” she says. “But I do think it happens more than we think.”

- This Could Be Us is published by Hachette Books Ireland, €17.99