Book Review: GUBU times of a grisly murderer expertly recounted

Malcolm MacArthur arrives at a court sitting in 1982. Pic: Collins

- The Murderer and the Taoiseach: Death, Politics, and Gubu — Revisiting the notorious Malcolm Macarthur case

- Harry McGee

- Hachette Books, €15.99

The words of one of the detectives who arrested Malcolm MacArthur in the penthouse flat of an exclusive gated community in Dalkey, Co Dublin in August 1982 have a haunting ring about them 40 years later: ‘This fellow when we caught him, he was a nobody’.

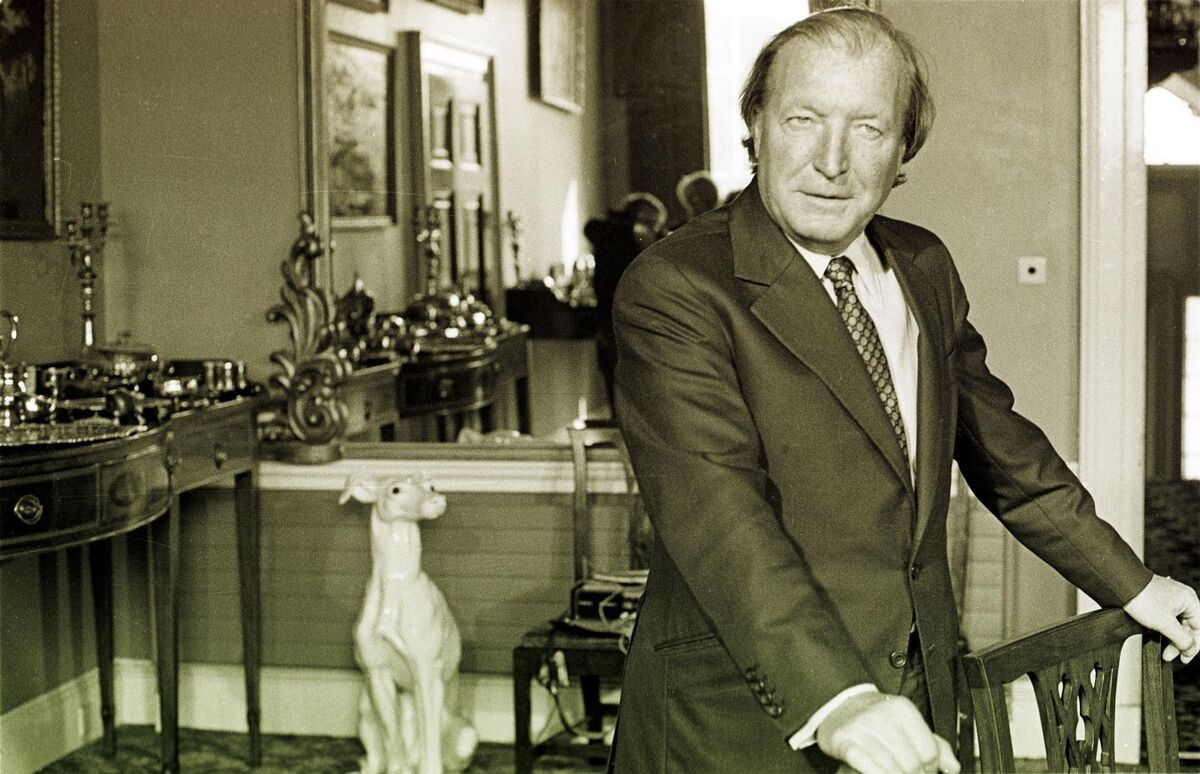

The fact that MacArthur, the killer of two young people — cut down in their prime — was caught in the flat of the state’s attorney general, Patrick Connolly, who himself had been hand-chosen for the job by Taoiseach Charlie Haughey, has endowed the case, and the events of that hot summer, with an almost mythical aura.

These grim events gave rise to the acronym Gubu — grotesque, unprecedented, bizarre, and unbelievable — which would forever shape memories of the era and the politician who defined it, Haughey.

That it was Haughey’s implacable foe, Conor Cruise O’Brien, who penned the fateful acronym would stick in the former Taoiseach’s craw for evermore.

Haughey had trounced Cruise O’Brien in a series of elections and treated him as a nobody, barely worth a second thought.

For his part, Malcolm MacArthur, wasn’t the nobody the detectives arrested in Dalkey on that fateful night but the killer of two young people, Bridie Gargan, and Dónal Dunne. For their families, he was the man who cruelly and inexplicably cut down their loved ones. And for what? Nothing it seems but that basest of motives; money.

In his riveting account of the events of the tragic murders of Gargan and Dunne, the manhunt for MacArthur, and the political crisis that unfolded after his arrest, Harry McGee observes that to the detectives who caught him, “the man who held Ireland in the grip of fear for over three weeks cut a pathetic figure standing before them now, a deflated-looking fool lacking guile or self-awareness. It was hard to equate this person with the cold brutality he had displayed.”

And MacArthur had displayed astonishing brutality in his cold-blooded killing of Gargan and Dunne in July 1982. Gargan, a nurse, was sunbathing on a glorious Friday evening in the Phoenix Park after a long shift at St James’s hospital when MacArthur beat her with a lump hammer in the back of her car.

Dunne, a farmer, callously gunned down with his own rifle which MacArthur had come to Edenderry in Offaly to purportedly buy. Both were hardworking members of society who had their lives shortened by a louche playboy type who had never worked a day in his life.

And all because MacArthur needed money. The inheritance he had received from his late father, an aloof austere figure, had run out and he got a hare-brained idea into his head that to get money he would rob a bank and to rob a bank he needed a car and a gun.

But for McGee, and indeed the reader, there is something inexplicable in MacArthur’s decisions to kill two innocent people. He could just have easily robbed Gargan’s car. She would have been shaken by the encounter where, on sunbathing, he came upon her, but would have survived to tell the tale had he just taken the keys and driven off.

Instead, he bundled her into the car and subjected her to a series of violent blows. He later dumped the car and left her to die in agony and loneliness on the back seat on a Dublin south inner city side street.

Two days later in a field in Co Offaly, when Dunne invited MacArthur to test the gun he could again have made a different decision to let the young farmer live and escape in his car. Instead, he shot him dead in cold blood and made his way back to Dublin.

McGee is very good on MacArthur’s background as the only child of wealthy but distant parents. There was domestic violence in the household and there is one truly pitiful scene of both the MacArthur parents driving past a young Malcolm in separate cars as he trudged the half mile to the bus stop to get to school.

A former farmhand describes how his parents would pass Malcolm on the road in hail, rain or snow without ever stopping to give him a lift. Sad and all as MacArthur’s childhood is, it offers no glimpse into the mind of this murderer.

In his confession to the guards, MacArthur described his actions as if he was an observer to them and after his first court hearing McGee evocatively describes him as “characteristically detached as if experiencing some interior version of events entirely at odds with the shattering reality unfolding around him”.

A shattering reality, albeit of a different kind, was also visited on Patrick Connolly, the state’s attorney general who was forced to resign in the aftermath of his guest’s arrest.

Connolly had been friendly with MacArthur’s partner, Brenda Little, for some time and through her had come to know the man whose name has never really faded from the public consciousness over the past 40 years.

MacArthur’s legal team, and perhaps he himself, thought his crimes would fade from the public view and that he would be a free man within a decade.

McGee, as befitting his status as one of the country’s top political journalists, is excellent on how the political and legal worlds intertwined in the aftermath of the trial. The decision by the state to accept a nolle prosequi in the case of Dunne, which continues to anguish his family, is particularly well covered.

To Connolly, MacArthur was bookish, reserved, a loving partner to Brenda, and their son. He had gladly let MacArthur stay as a guest in his home in Dalkey when he arrived from Tenerife in the summer of 1982 on the pretext of getting some financial affairs in order. MacArthur had told Little that he was in fact in Belgium again sorting out his finances.

Neither Connolly nor Little had any idea of what Macarthur was up to. McGee postulates the theory that MacArthur himself had no real idea of what he was up beyond his madcap scheme of robbing a bank, an idea he got from reading about the IRA’s expertise in this area.

Nobody can really know what MacArthur thought when coming upon Gargan and Dunne as the killer has never spoken of these events. But from McGee’s dramatic account, it is reasonable to suggest that a number of other people who came across MacArthur had lucky escapes.

This was particularly so of a former American diplomat, Harry Bieling, who made a daring escape when MacArthur, a few days after his gruesome killing spree, had inveigled his way into his house and, at gunpoint, demanded the princely sum of £1,000.

McGee eloquently describes the relationship between Connolly and Haughey and the almost ludicrous way the events of the story spun out of the control of both men in a tale of antiquated phone lines, miscommunications, stubbornness, poor judgement, and downright bad luck. His

judgement on Haughey, in particular, is shrewd and acute.

McGee is a natural storyteller with a telling eye for detail, and he recounts the tale with gusto.

However, his greatest service is perhaps to the families of MacArthur’s victims, Bridie Gargan and Dónal Dunne. In the last words of his riveting book, he reclaims them as people in their own right.

They are no longer just footnotes to the story of a pathetic murderer who committed appalling and, to this day, still inexplicable crimes, but people who loved and were loved.