Eoghan Daltun: My 10 favourite nature books

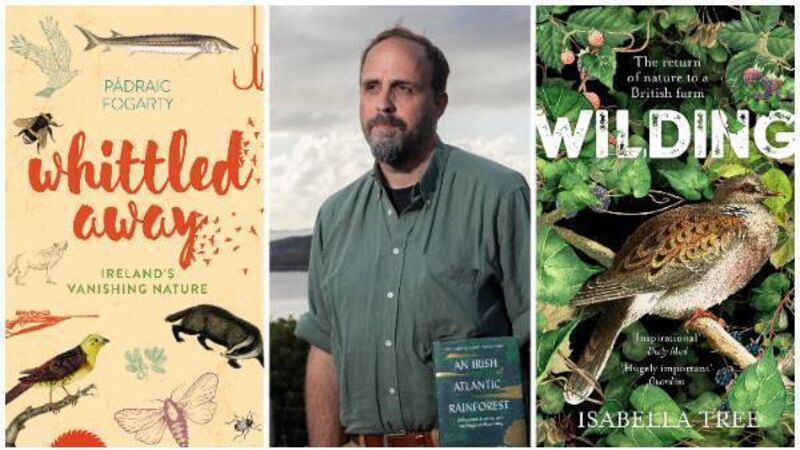

Eoghan Daltun is author of An Irish Atlantic Rainforest.

I love reading, and I think this helped enormously when I decided to write my own book, An Irish Atlantic Rainforest: A Personal Journey into the Magic of Rewilding (Hachette Ireland, which was published last September.

But I only go for non-fiction; the last real fiction I read was probably a decade ago or more now. I went through a long period of reading mostly books about the natural world and ecology, as I was working to restore my own rainforest, and was fascinated with how ecosystems work.