Book Review: The McCartney Legacy is a welcome addition to The Beatles canon

Book Review: It's all about Paul in the latest addition to the Beatles canon

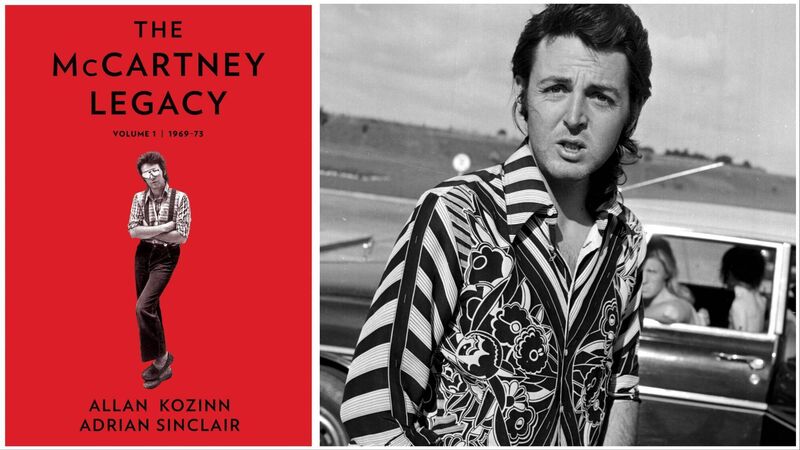

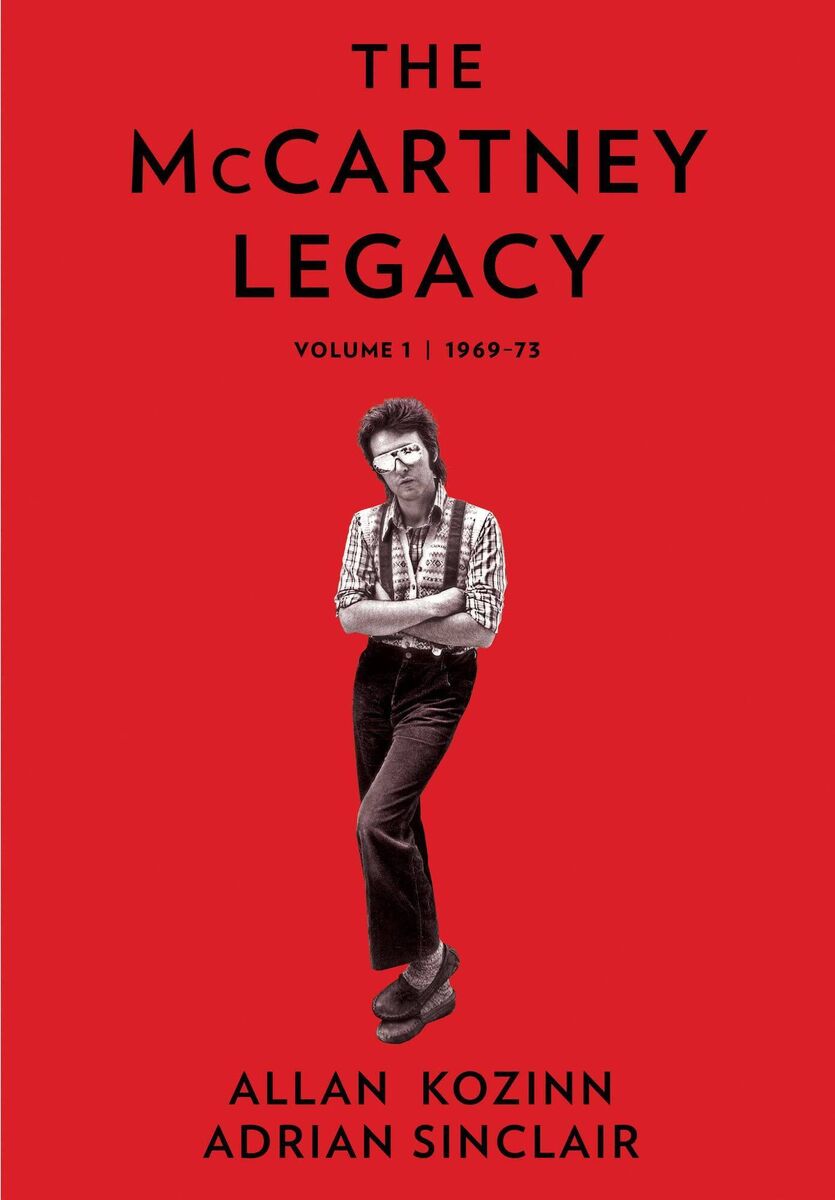

- The McCartney Legacy, Volume 1. 1969 - 1973

- Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair

- Harper Collins, £30

Ian MacDonald’s , published in 1994, and , Philip Norman’s 1981 biography of The Beatles, are the best of the mountain of books about the greatest pop group of all time and it’s an exceptional body of work.

One might legitimately argue that far too much has been written about The Beatles, the most profoundly influential band in the history of modern music, but it takes no little genius to shake the world.

Making sense of the how and why has consistently occupied writers, academics, critics, film-makers and fans, spawning a lucrative side-industry of its own.

Together for less than a decade, the fascination with The Beatles — and especially their principal song-writers, John Lennon and Paul McCartney — shows no signs of abating.

The challenge, therefore, for co-authors Adrian Sinclair and Allan Kozinn is obvious: by putting Paul McCartney’s 50 years of solo material under the microscope, what do we see now that hasn’t been apparent before? A challenge made all the more invidious, you’d think, by the recent publication of , to all intents a two-book McCartney autobiography, co-written with the poet, Paul Muldoon.

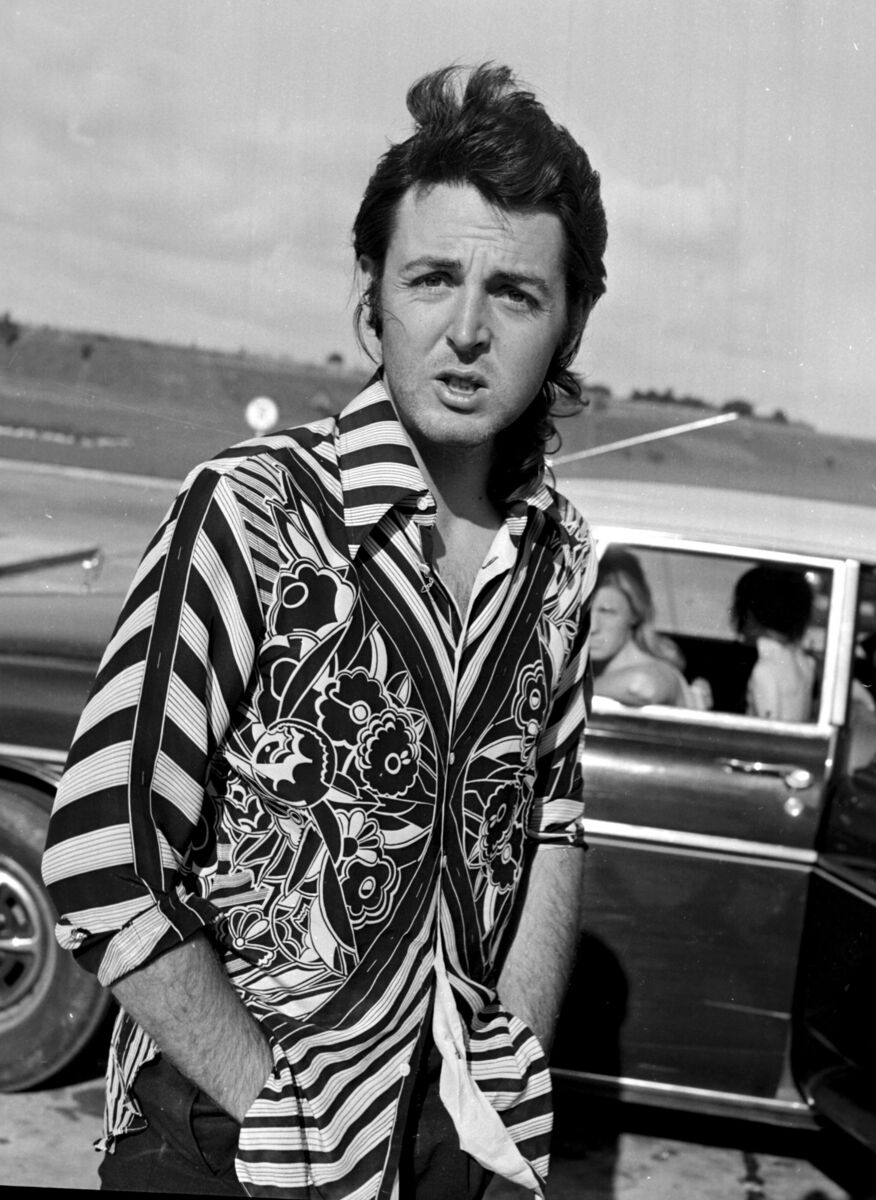

The authors rise to the task in detail, literally. As one might expect from a 700-page deep dive by two seasoned researchers and documentarians, they’re clinical in their work here, the first in a planned series of critical contextualisations of McCartney’s life and work. Set during a messy transitional junction immediately after the unravelling of The Beatles, it begins with the scattergun origins of his eponymously-titled debut solo album in 1970.

Within three years Paul goes on to makes three albums with a new band, Wings, and completes five post-Beatles LPs, all of which are forensically deconstructed here.

McCartney at his most prodigious, hungry, lusty, adventurous and vulnerable provides the authors with a fertile starting position and they capitalise on it with gusto. Awash with minutiae — maybe sometimes overly so? — it’s gossipy yarns and keen critical eye ensure that maintains its momentum over the distance, even without direct input from the subject himself.

But the real insight emerges from personal sources and archives: studio booking forms, diaries, notes left behind on ancient recordings and the first-person testimonies of young studio operatives, Alan Parsons and John Leckie among them.

Explicit testimonials from a distance by numerous musicians and assorted hangers-on lift it well into the major leagues.

In one memorable passage, the late Northern Irish guitarist Henry McCullough, calls McCartney ‘a cunt’, walks out of a testy rehearsal with Wings and never returns. Elsewhere, the allusions to Paul’s personal life — his drinking, drug-taking, temper, and especially his obsession with money — are enough to keep the floating reader engaged while still appeasing the fanatical element that McCartney attracts in droves.

For 50 years, Paul McCartney’s body of work has been consistently re-appraised and re-evaluated: with the exception of another octogenarian, Bob Dylan, no musician has been pored over so obsessively.

Having been condemned initially to the critical naughty step in John Lennon’s shadow, most notably by Philip Norman, his re-casting as his writing partner’s creative equal has been a long, slow and complicated trip. Peter Jackson’s excellent television series, , which premiered last year, only served to remind us of that.

But raises those stakes again and, in so doing, puts real flesh on what has often been a crudely-formed, thumbs-aloft, cheeky-faced stereotype. As such it’s another welcome companion piece to the more provocative wing of the McCartney library.