Philippe Auliac: The man who photographed David Bowie

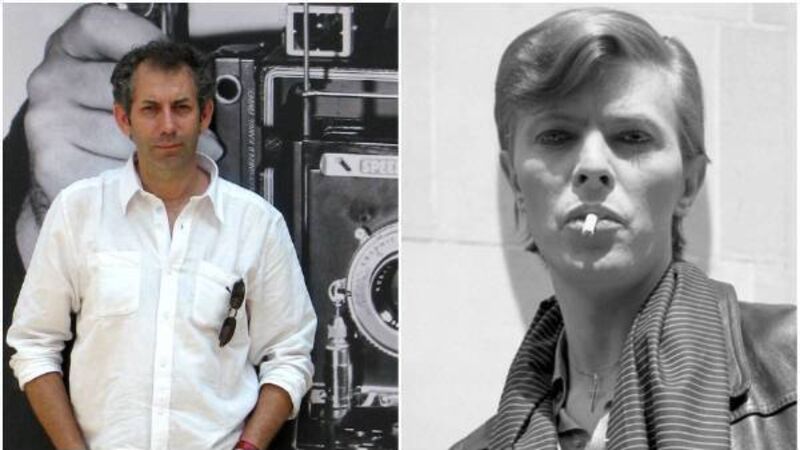

Philippe Auliac has an exhibition in Dublin as part of Dublin Bowie Festival. (Picture: Laurence Geslin); right, one of Auliac's pictures of Bowie.

In 1976, music photographer Philippe Auliac went to Berlin to visit his friend David Bowie. At that time, Bowie was in the middle of one of the most dramatic reinventions in rock history, as he recorded his moody ‘Berlin’ trilogy – starting with the avant-garde classic Low.

Auliac had a ringside seat as a masterpiece took shape. It did so at the Hansa Studios complex in the shadow of the Berlin Wall. Bowie was collaborating with former Roxy Music keyboardist Brian Eno and his long-time producer Tony Visconti. Together they wove a dark alchemy from the Cold War gloom.