A rich tradition: UCC marks 100 years of Irish music at the college

Participants in a recent concert at the Aula Maxima in UCC to mark 100 years of traditional music at the Cork college. Picture: Ruben Martinez/UCC

A century after the appointment of its first professor of Irish traditional music, the subject is accorded parity of esteem at University College Cork, where its status is now “on an equal footing with any other music”.

That is according to uilleann piper Mary Mitchell-Ingoldsby, lecturer at the university’s Department of Music, where as a student she had been the first to play an Irish traditional instrument as her main instrument for a Bachelor of Music degree.

How music handed down chiefly by aural tradition gained a new respectability in academia is the story of many such firsts at the university, where a series of incremental steps and influential appointments have positioned jigs and reels alongside symphonies and sonatas in terms of musical prestige.

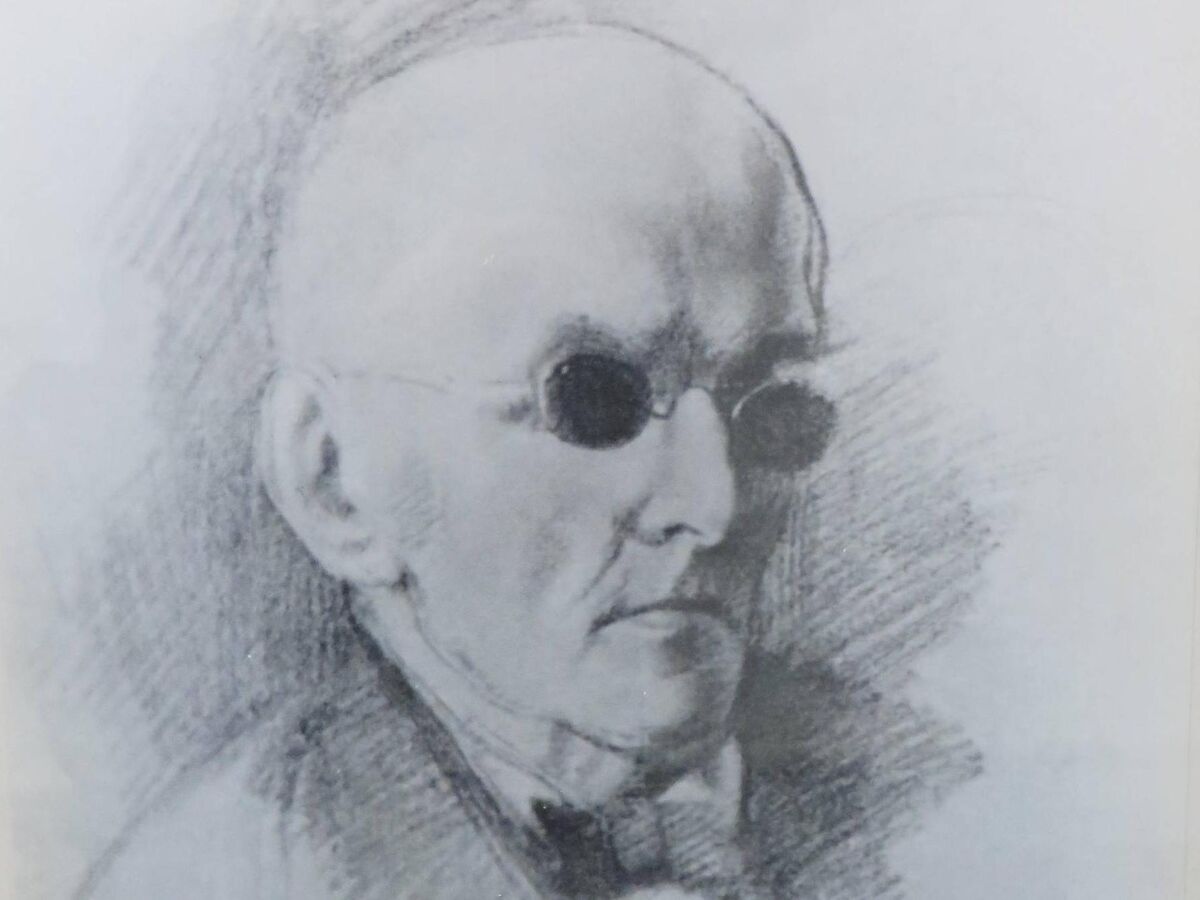

From the 1922 appointment of composer and music collector Carl Hardebeck to the impending development of a taught masters degree in Irish traditional music, the subject has been a “continuous and important part of the curriculum,” says Mitchell-Ingoldsby.

The appointment of Hardebeck came about following a request by Cork Corporation for the university to establish a professorship in Irish traditional music and represented “the first time in any Irish or European university where the traditional music of its country was an integral part of the curriculum,” she adds. “Since then we have had an unbroken tradition.”

Hardebeck was a London-born folk music revivalist who was also blind. He “brought our Gaelic airs into the concert hall, into the schoolroom, into the church and into the home”, according to Seán Neeson, one of his successors, departed after a year in the role.

The death of Hardebeck’s immediate successor, Dr Annie Patterson, saw the appointment of Belfast harpist and singer Neeson as lecturer. A Sinn Féin member imprisoned during the Civil War, he went on to become director of Radio Éireann in Cork and was married to pianist Geraldine Neeson, past pupil of Tilly Fleischmann.

The Fleischmanns, “would have been friendly with people like Tomás Mac Curtain, Terence MacSwiney, Daniel Corkery, and other literary figures who were nationalists as well,” says Mitchell-Ingoldsby, who sets Cork’s prominence in the study of Irish traditional music against this background of Gaelic cultural nationalism.

Tilly’s son, Aloys Fleischmann, professor and head of UCC’s music department from 1934 to 1980, while famed as a classical composer, conductor, and founder of Cork Symphony Orchestra and Choral Festival, spent almost 40 years researching his encyclopaedic ‘Sources of Irish Traditional Music 1600-1855’.

That work was assisted by Seán Ó Riada and Micheál Ó Súilleabháin, who both went on to make their mark on the teaching of Irish traditional music at UCC.

Ó Riada, appointed in 1963 and the first lecturer in Irish music sponsored solely by UCC, rather than Cork Corporation, “decided that his students, as part of the Irish music module, should play traditional music on a traditional instrument”.

“Most of the students up to that stage would have come from a Western art music background,” says

Mitchell-Ingoldsby, “but Ó Riada said everybody should play one or two tunes on a traditional instrument so that they would gain an understanding of it”.

Following Ó Riada’s death in 1971, his former student, uilleann piper Tomás Ó Cainnín took over his traditional music role on a part-time basis while also lecturing in electrical engineering, and in 1975 came the appointment of Ó Súilleabháin, later head of music.

He built on Ó Riada’s foundations in music performance. “One of the first things that Mícheál did was to invite a tutor in Irish traditional music to teach traditional performance and that was Mícheál Ó Riabhaigh, who taught the students tin whistle as part of the course,” says Mitchell-Ingoldsby. “Fiddle was the next instrument taught and by 1983 there would have been uilleann pipes, button accordion, and set dancing, then harp and singing.

“Curricular reform and development was very much part of Mícheál’s work and included a greater element of choice for students.”

Previously, there had been “a lot of set courses and the slant was very much towards Western art music, whereas now there were more courses on offer and then as time went by these courses were given stronger credit ratings.

“There was parity of esteem by the early 90s between all music studies, rather than one type of music being the ‘important type’,” she says. “Slowly but surely, as the course began to change, traditional musicians began to come to the department and there were more performance courses offered.”

With Ó Súilleabháin departing for the University of Limerick in 1994 his former students took over lecturing duties, Liz Doherty establishing the group Fiddlesticks, Mitchell-Ingoldsby working on UCC’s music archive, uilleann pipes research and performance courses, and Mel Mercier furthering curricular reform as head of the new School of Music and Theatre.

Aileen Dillane, appointed in 2003, was integral to the development of UCC’s first taught MA in ethnomusicology, while sean-nós singer and whistle-player Tríona Ní Shíocháin taught the country’s first music module through Irish, with Michelle Finnerty now working in community music engagement and Jack Talty appointed lecturer in traditional music.

Further innovations included the extension of the BMus degree to four years, while Arts Council funding since 2012 has facilitated the appointment of traditional artists in residence, the first of them singer Iarla Ó Lionáird and the current incumbent Caitlín Nic Gabhann.

Over the course of a century, UCC’s Irish traditional music studies have developed alongside the rising status of the music, which now commands “much more respect amongst the general population,” says Mitchell-Ingoldsby.

“There are more staff, with different skill sets, and our students come with different needs and strengths. There are more modules, more choice for students, and we like students to delve into other types of music because it informs their traditional music.

“One of the things that is very important to all the staff is that there is parity of esteem between all musics. Giving traditional music status and standing and giving it its place amongst music studied at university level has been very important - and it’s where it should be.”

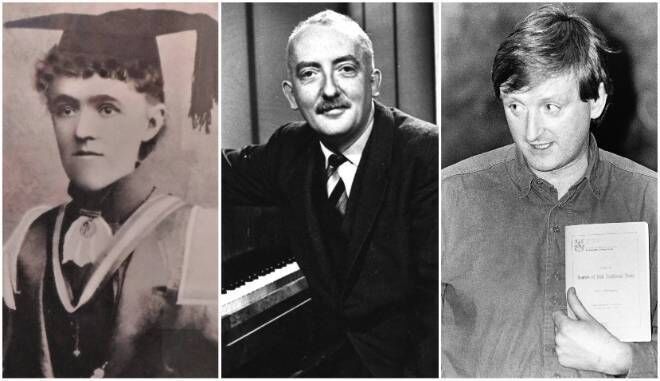

, a Protestant of Huguenot descent, was appointed music lecturer at UCC in 1923. An “amazing lady”, according to lecturer Mary Mitchell-Ingoldsby, “she was a scholar, composer, Irish traditional music promoter and arranger; an organist, and she was the first woman in Ireland or Britain to be awarded a PhD in music, that was not an honorary degree”.

Prominent in the cultural revival of the 1890s, she was among the founders of the Feis Ceoil and Oireachtas na Gaeilge, having “learned the Irish language, believing that the music and the language were intrinsically linked”.

She became “very much involved in the cultural life of Cork; wrote 10 books on music, and she composed music, songs, two operas, and taught composition and Irish traditional music”.

was appointed lecturer in Irish traditional music at his alma mater in 1963 following Seán Neeson’s retirement. “The job was coming up and [Aloys] Fleischmann was anxious that Ó Riada would get it because he felt that he would really instil a love of the music and inspire the incoming students,” says Mary.

Ó Riada, who with his group Ceoltóirí Chualann presented traditional music in new ensemble style with a nod to jazz improvisation, “had a lot of knowledge, especially from his own research for his radio programme Our Musical Heritage”.

A “very charismatic teacher”, the Mise Éire composer gave his UCC students “a great love not only of the music but also the language and culture. He began speaking Irish to them and they all started adopting the Irish form of their names,” she adds. “They studied sean-nós songs, uilleann piping, different regional styles, and the ornamentation used by pipers and fiddlers.”

arrival in 1975 saw the introduction of tutors teaching the practical skills of traditional music. He placed emphasis on field work and the documentation and preservation of traditional music, equipping students with high-quality recorders to gather material for UCC’s traditional music archive.

He encouraged students to set up a harp society and in 1980 an Irish traditional music society, believed to be the first of its kind in an Irish university. During his tenure the music entrance exam was changed towards the practical, with potential, as well as current prowess, taken into consideration.