'The band is formally stopping': Horslips reach end of the road

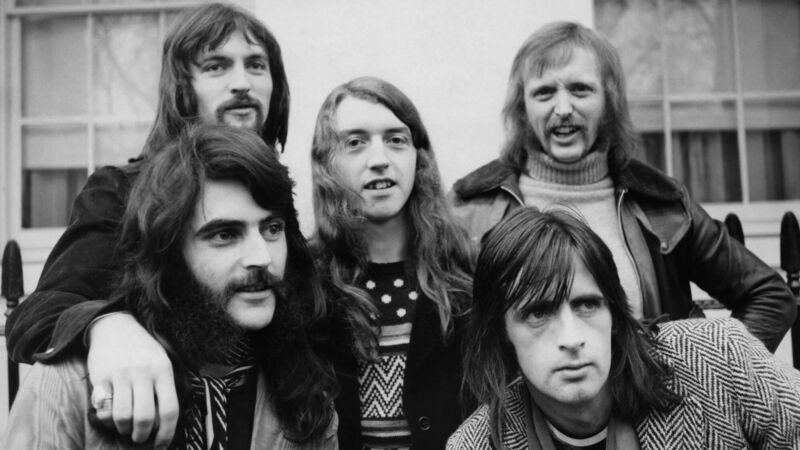

Horslips in 1974: Jim Lockhart (behind), John Fean, Barry Devlin, Charles O'Connor and Eamon Carr (behind). (Picture: Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

On November 16, at the Ulster Hall in Belfast, Ireland’s original Dancehall Sweethearts take one final twirl. Horslips, the long-haired psychedelic warriors of Seventies Celtic pop, play what is being billed as their last-ever gig. It promises to be an evening high on emotion and super-charged with nostalgia.

“The band is formally stopping in Belfast,” says singer and bassist Barry Devlin. He’ll be performing with keyboardist and flautist Jim Lockhart, a fellow Horslips founder member, and with friends of the group Ray Fean and Fiach Moriarty [the rest of the classic Horslips line-up having retired]. “It’s last gig time.”