Culture That Made Me: Colm Tóibín on Hemingway, sean-nós and cinema

Colm Tóibín. Picture: Barry Cronin

Colm Tóibín, 67, is one of Ireland’s greatest living writers. He grew up in Enniscorthy, Co Wexford, which is the setting for several of his novels, including Brooklyn, which was made into a popular film starring Saoirse Ronan. In 1982, he became editor of Magill Magazine. Later, he published several acclaimed non-fiction and travel books. In 2006, he won the Dublin Literary Award for his novel . He lives in Los Angeles.

I loved the Agatha Christie novels growing up. Maybe one in particular, with a wonderful title: . I found them exciting. The plots always puzzled me. I never would predict who did the murder. It was always someone surprising. They were the first books that really interested me. There was a certain picture of English life – I mean the whole business of the vicar, for example – which was far away from my childhood in Enniscorthy. It was quite exotic.

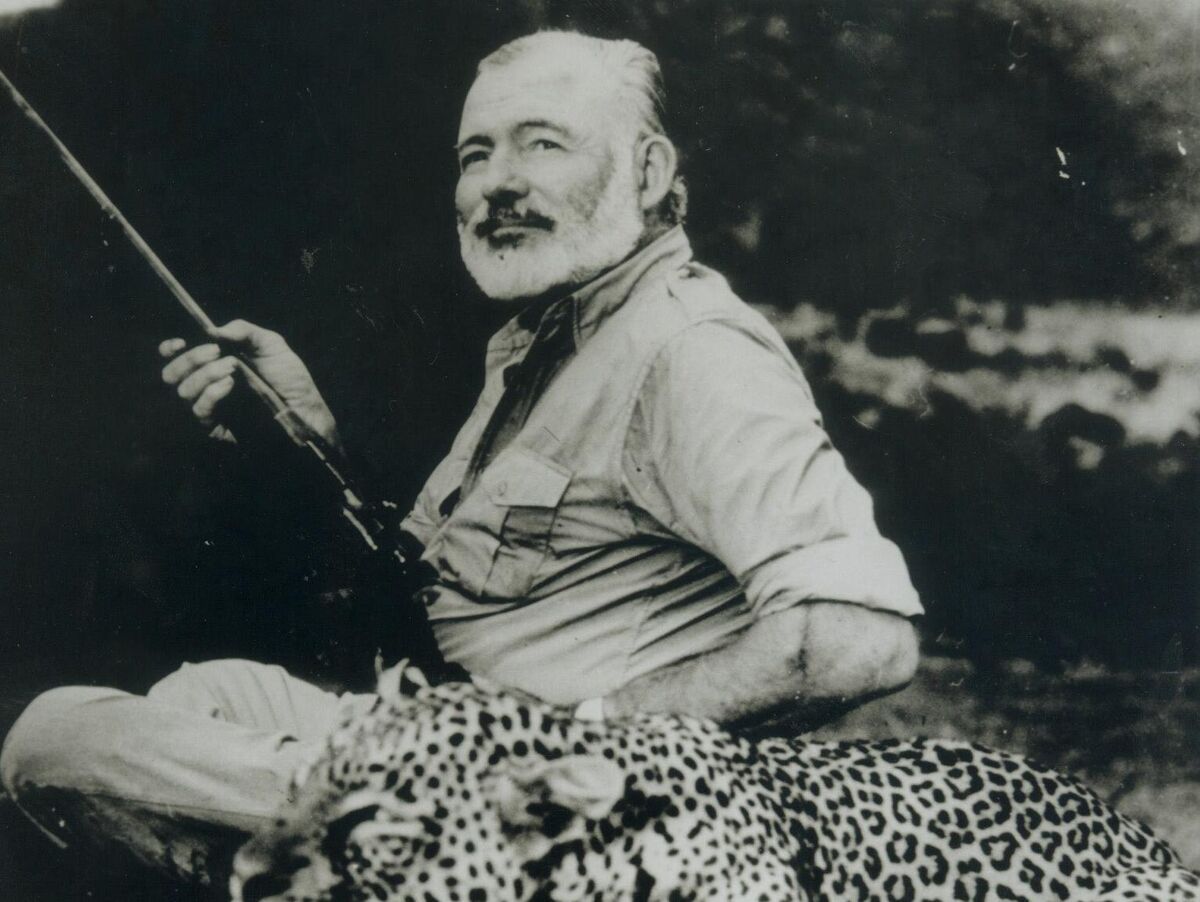

Reading Ernest Hemingway’s , which I would have done aged about 17, was influential. I found the style interesting, the simplicity of it. The way he presents the character of Jake, who is such a watcher, a noticer. He's standing outside the group a lot of the time. Hemingway makes him accessible to any reader – that you can see poor old Jake, how he is suffering. He's a modern fellow. He suffers as much as he enjoys.

I read Richard Ellman’s biography of James Joyce when I was 19 or 20. It’s a tremendously interesting book. I read it before I read . It was close to home in some ways – the childhood, the education, the way that Ellman could write both about the life and about the work. I remember particularly being struck by his description of the story , but also fitting it in all the time into how Joyce had lived his life. It was a fascinating book.

There was a wonderful cinema in Dublin in the 1970s called The International. It was in Earlsfort Terrace – the space where The Sugar Club is now. They would change the film every week and it would be something terribly interesting. Before even the word arthouse came up. On Thursday night, you would see the new sign going up about what it was going to be. It was a heroic period of film. You were seeing the new Fellini, the new Bergman, the new Polanski films. Also Éric Rohmer, Luchino Visconti. Oddly enough, I'm stuck in that period. I never developed after that. I always expected that life was going to be like this – that there would be a new, wonderful film opening every week. That didn't turn out to be true.

There’s a scene in Fellini’s where they all masturbate. That was cut in the Irish screening. I mean literally with the scissors by the Irish censor. I didn't know that scene was in the film until I saw the film years later. I thought, I don't remember that. The scissors was so badly done sometimes that you could notice the incision. A big cheer would go up in the audience. A cynical cheer: how tiresome this is to be in a country where a man sat in a room with a scissors and cut the bit that you most wanted to see in the film.

In my mid-20s, I read a lot of Norman Mailer’s books: , which is a description of the anti-Vietnam protests and another book , which is about the 1968 Republican and Democratic Conventions. He put himself at the centre of the picture. He was unembarrassed about this. He was a bulky, boastful figure. He was always trying to be great in some way. I admired the sense of energy in the writing, the sense of newness. The presence of the writer, how that was managed, the way he dealt with political things in a quirky and interesting way.

Joan Didion was a beautiful stylist, both as a novelist and as a nonfiction writer. Her nonfiction had more impact: her books and another one, . More than Mailer, Didion was a watcher. She was someone who sat back and noticed. She placed herself at the centre of her nonfiction, but in a different way to Mailer, who was always making noise. Didion was often silent – this neurotic figure wandering through, watching the Doors recording an album in an iconic, distant, knowing way. Her nonfiction was very exciting to me.

I started to read Henry James aged about 18 or 19. The novel I wrote, , arose from reading him in those years. I found the style in beautiful. There is an elegance in the way the sentence-making is done. It seems at the beginning to be a novel about style and someone from America coming to England, and the difference between the two countries, but it turns out to be a novel about treachery. Quite a moral novel about good and evil. I didn't see the plot coming. I was blindsided. I found that intriguing the way that something was happening, but I didn't notice it.

The figure that intrigued me most among travel writers was V.S. Naipaul. He wrote novels and travel books, including the marvellous travel book , about when the Ayatollah came to power in 1979, while he was travelling through Muslim countries like Malaysia and Iran. There's another book of his that I admired called , which is an account of being in Argentina during the time of “the disappearances”. Naipaul had a commanding, magisterial style and a sense of history.

Popular culture is designed just to brighten your day: beach novels, bright pop bands, advertising. There is a need for something to bring in sadness and give you some other perspective on life other than it's a nice happy thing and you should go shopping. There are so many jingles. Finding something that's not jingle deepens your experience of life. That’s what sean-nós does. There are so many sad songs in Ireland. They’re there for a reason. I find the level of dedication of those artists to get things right – Joe Heaney, Caitlín Maude, Mairead Ni Dhomhnaill – impressive. It’s as though they're making songs for each other. They’re connoisseurs.