Book review: A delightful and definitive biography of surrealist René Magritte

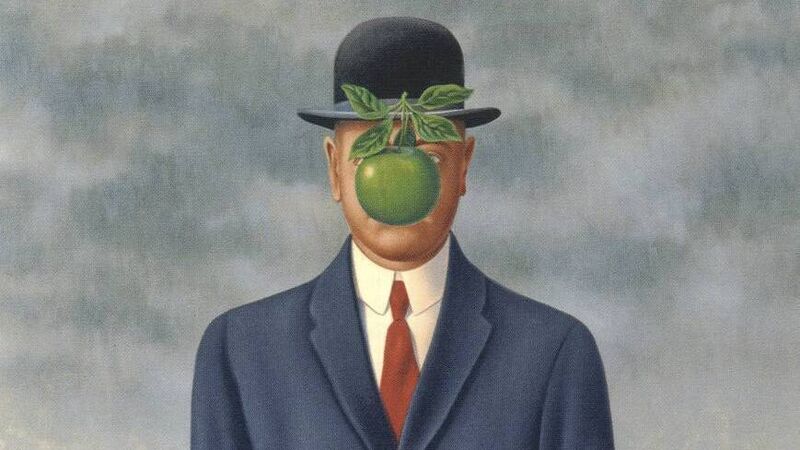

Detail of René Magritte’s ‘The Son of Man’ (1964): The bowler hat in this and other paintings cannot help but amuse. Is it a joke against the bourgeoisie or is there a reference to Charlie Chaplin’s character, the Little Tramp?

A question asked repeatedly as a joke: How many Belgians can you name? Well, here is one: René Magritte, surrealist.

Alex Danchev, author of Magritte: A Life, may not be a household name but is well known in academic cloisters as he has held lectureships, fellowships, and professorships. Danchev’s mother was from Lancashire, but his father’s heritage was not only Belgian (that’s two) but also Bulgarian: he immigrated to the UK in 1939 becoming a citizen in 1945.