Book Interview: Cónal Creedon - an accidental author, and the real deal

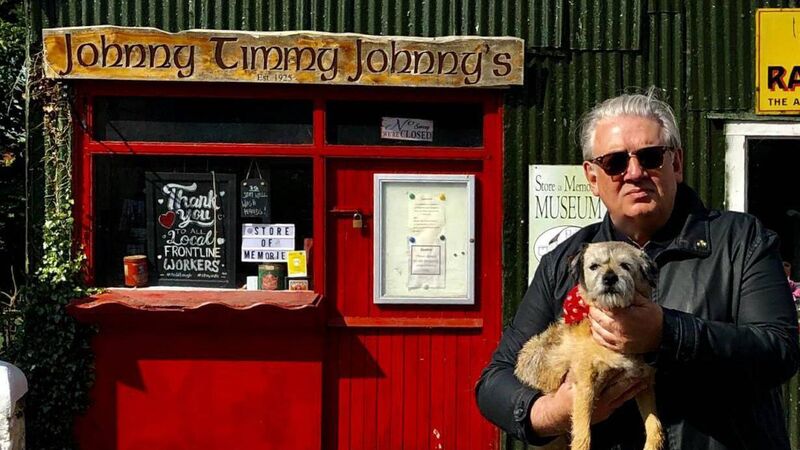

Cónal Creedon and Dogeen outside Johnny Timmy Johnny's in Inchigeelagh.

RECALLING the lively launch of his short fiction collection, 'Pancho and Lefty Ride Out' in Murphy's Brewery twenty-five years ago, Cork writer, Cónal Creedon says: "The whole town was there, Mick Hannigan, Máirín Quill..." His voice tapers off as he remembers the crowd.

On the other hand, the recent launch of the re-issued collection, 'Pancho and Lefty Ride Again' (with some add-ons) at Waterstones in Cork, was a sober affair.

In keeping with Covid restrictions, there was a small number of chairs to sit on, people wore masks and there was no vino. But there was some craic. Creedon and some of his cronies repaired to the Bodega afterwards to mark the occasion.

Chatting animatedly in his inner city home that resembles a film-set type bordello with dark red walls, lots of gilt framed art, curvaceous furniture and dainty tangerine and white china cups and saucers, Creedon serves coffee and becomes quite philosophical. Some would say he borders on the morbid.

Having recently hit the landmark age of 60, Creedon tries to convince himself that "age doesn't mean a thing." But talk soon turns to death. "I suppose living next door to a funeral parlour (on Coburg Street), I'm really very comfortable with the whole nature of death." Even his own death?

"Yeah, except I'll miss people. I wouldn't be a great believer in what's coming next. I really don't care if there's something or there isn't. It's all part of the adventure. But what really amazes me about the whole death thing - and maybe this comes with being sixty - is the realisation that we're the only animals in the world who know we're going to die. No matter how sophisticated a dolphin is, he has no concept of his own mortality."

How does awareness of our mortality affect us?

"All the old guff that we think is really important; politics, arts, government and massive debates, maybe that's a process in our heads to create a load of white noise."

Creedon suggest it's a way of deflecting from the inevitability of death. He adds that if we were to learn anything "from those things, we'd be very different now. But we keep doing the same thing over and over again, back to the forties and what happened in Europe. A recurring theme throughout history is that people cause chaos and everyone reacts to it. Millions die. We go back to normal. We think everything will be wonderful. God knows, it's probably heading in that direction again. We have a huge capacity to deceive ourselves."

Creedon doesn't go around spouting his politics, saying he's more of an observer and is all too aware of how things can change very quickly. But one issue he feels strongly about is the inhumane system of direct provision.

"Everyone is up in arms over the mother and baby homes and rightly so. But there is something right now that we can do something about and that's direct provision. What's happening is a human construct and it's not fair. There's that whole thing of thinking that 'it's out there' when it's actually here. That's like part of the death denial thing."

Asked why he republished his short fiction collection, this time by his own company, Irishtown Press, Creedon doesn't admit to hoping for immortality through his writing. Self-effacing in person (though a prodigious self-promoter on Facebook), he explains that he merely wanted a copy of the book having long mislaid (or lent out) his own copies.

He mentioned it on social media and got the impression that there was a lot of interest in the book. But when he dug a little deeper, Creedon realised that the era in which the stories are set was of more interest than the narrative. Although published in 1995, the stories were written during the eighties in Cork.

"The eighties were derelict. I came back from Canada because my mother was seriously ill. The quay had literally fallen into the river outside the Quay Co-Op and at the end of the Coal Quay. Tar barrels were put there for safety. You could get money from Europe for structural jobs, building highways, but you couldn't get money to fix up what was falling down. "

Creedon, whose mother died a year after he returned to Cork, recalls the bundles of newspapers that she used post to him when he lived in Newfoundland, "studying whatever came my way, life in general."

The author of two novels, with a third almost completed, several plays - performed on the stage as well as on radio - Creedon also makes documentaries including one of the burning of Cork. And he was the author of a cult soap that ran for years on RTÉ Radio Cork.

It is, he says, difficult to make a living from writing but he has "been lucky." Creedon ran a launderette during the early years of his writing career. Not that he thought he was embarking on a career as a scribe. He had no plan and no ambition.

In the introduction to 'Pancho and Lefty Ride Again', Creedon writes: "I moved from scribbling at the counter of my launderette to the relative comfort and privacy of writing in my old clapped-out Volvo parked outside...I became an accidental author."

These days, Creedon is the real deal. He writes full-time, starting his working day at 4am, getting a fair whack done during the slow dawning of the day and generally retiring to bed around 8pm, having done the shopping and looked after administrative tasks.

Comparing the arts as practised today compared to the eighties, Creedon says they have become "incredibly industrialised. Back then, we wouldn't have had arts administrators. There wouldn't have been an arts officer in City Council. You'd have to go to your local councillor to see if they'd support something you were doing. There wouldn't have been Arts Council funding at the level there is today.

"Even the publishing industry seemed to be more of a cottage industry. It wasn't really driven by agents. That seems to be a whole layer that I personally find inaccessible. I just want to write my stuff."

The eighties were also a time of the cheap bedsit. "Those places don't really exist anymore. The thing about bedsit land is that we've all been there in some shape or form, as a guest or an inmate. For a short time, I rented one on Wellington Road. You could get those places for a tenner a week and you didn't need any references. You needed two weeks rent in advance.

"£20 was manageable. Even people who were casualties of society could manage to put a roof over their head and live within the parameters of their casualty, be it addiction or whatever. Now, if you're young, you can't actually access your own place."

Creedon shows me a 'Cead Míle Fáilte' sign, complete with harp and shamrocks that hangs over the archway between his kitchen and sitting room. It was left to Creedon by the late republican, Denis Griffin, who ran a shop, 'An Stad' with his sister, Noreen, across the road from Creedon.

Creedon worried that Griffin would dislike the reference he made to him in his Christmas story, 'Come Out Now, Hacker Hanley!'" But there was no problem. It's a charming seasonal story that is all about belief in the extraordinary. Creedon is a sucker for Christmas. There's still a bit of the child in him...

- Pancho and Lefty Ride Again by Cónal Creedon is published by Irishtown Press