Book Review: a Spanish captain's account of 1500s Ireland

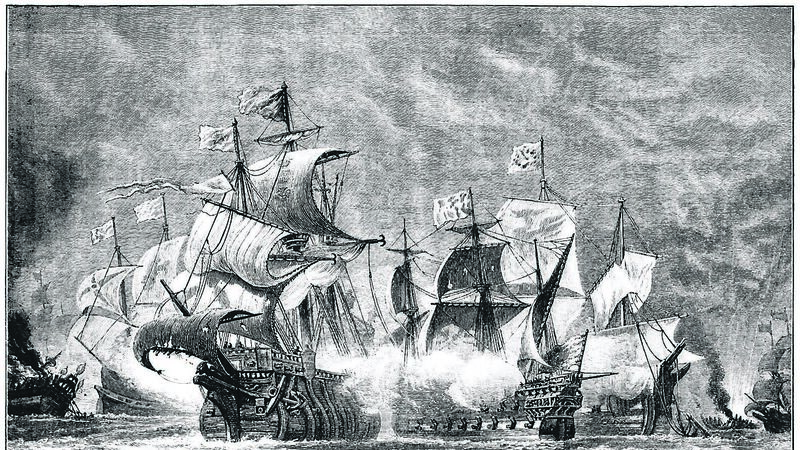

Fighting between the English fleet and the Spanish Armada during the abortive attempt by Spain to invade England in 1588.

- Captain Francisco de Cuéllar: The Armada, Ireland and the Wars of the Spanish Monarchy, 1578-1606

- Francis Kelly

- Four Courts Press, €31.50

- Review: David Kernek