John Creedon: Why our place names say so much about us

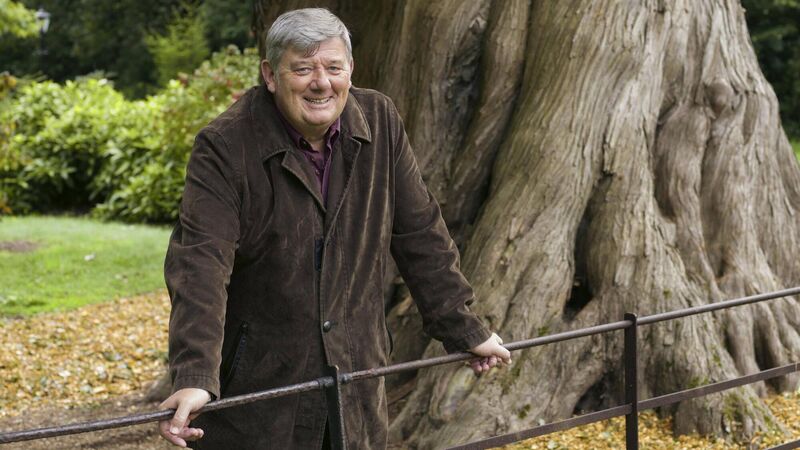

John Creedon, broadcaster and author of That Place We Call Home. Picture: Don MacMonagle

“As a kid, in my head, I was always doing little mini-tours,” says John Creedon with a laugh. “On my way to school, I’d be bringing some imaginary Yank on a tour of Cork.” Warming to his theme, he launches into an improvised monologue.

“This is Roman Street, they’re all holy names around here, Redemption Road, Assumption Road, Ascension Place’ or ‘This is the brewery, Cork has two breweries, Beamish on the southside, and Murphy’s on the northside, and interestingly, Murphy’s was owned by a brother of the Bishop of Cork, and his other brother was the man who started the distillery in Midleton…”