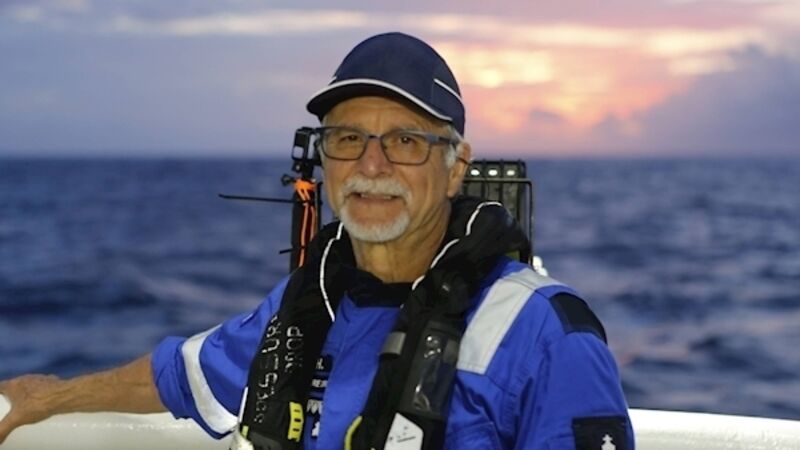

Titanic wreck diver Paul Henri Nargeolet: 'In deep water, you’re dead before you realise it's happening'

Paul Henri Nargeolet is matter-of-fact - nay even jolly - when discussing the risks associated with his work.

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBEThis article was first published on October 7, 2019. Paul-Henri Nargeolet is believed to be on board a submarine that has gone missing during a tour of the Titanic wreckage.

Paul Henri Nargeolet is matter-of-fact - nay even jolly - when discussing the risks associated with his work.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

The best food, health, entertainment and lifestyle content from the Irish Examiner, direct to your inbox.

Newsletter

The best food, health, entertainment and lifestyle content from the Irish Examiner, direct to your inbox.

© Examiner Echo Group Limited