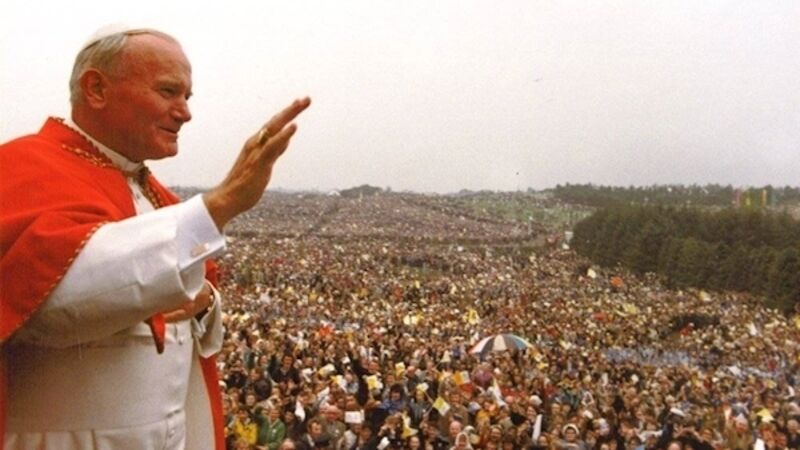

Ask John Paul: Men who share the Pope’s name on the big changes during their lifetime

40 Years after the visit of Pope John Paul II to Ireland, looks back at that era and asks men who share the Pope’s name what they think of the big changes during their lifetime

IRELAND, 1979. Women looked like Joanna Lumley in the New Avengers; men looked like they had slept in a hedge.