Documentary offers different ways of seeing mental illness

In the West, having a ‘breakdown’ is a medical condition, but in other societies, it can be regarded as a spiritual experience.

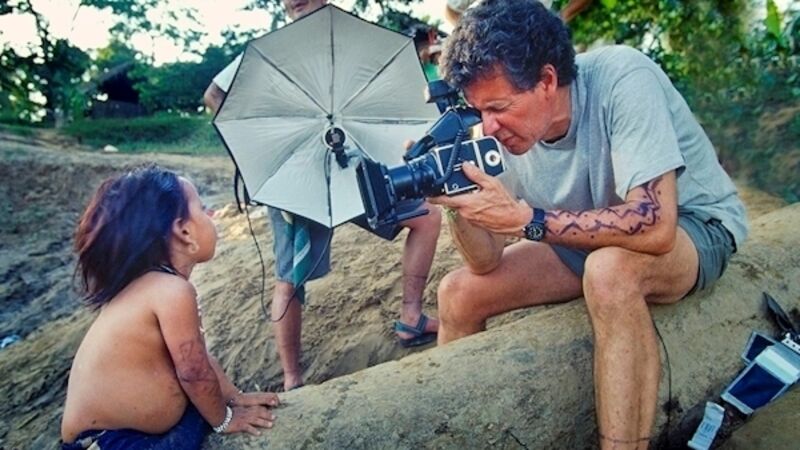

A documentary showing in Cork this week wonders which is truer, writes .