Shandon Sweets reveal their 'secret mixture'

Under the shadow of Shandon’s steeple, in one of the oldest part of town, as the bells ring out the perfect sound of Cork, the morning air on John Redmond Street is filled with a warm, sweet smell from childhood.

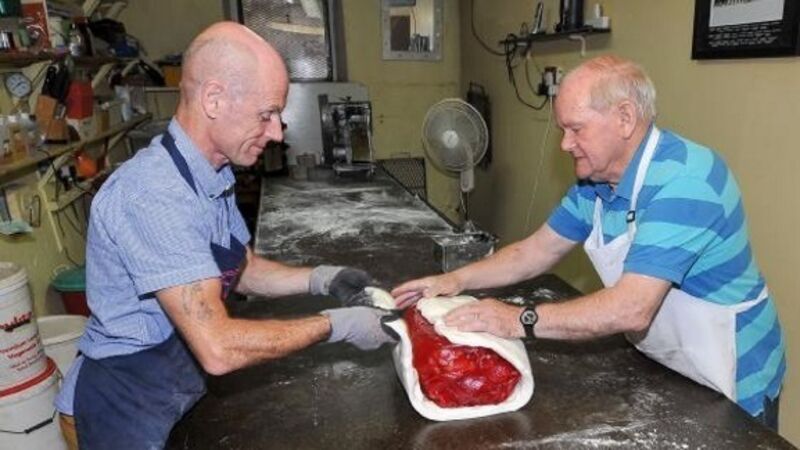

At the doorway of Shandon Sweets, the sweetshop that time forgot, Danny Linehan welcomes visitors to the last remaining hand-made sweet factory in Ireland, the business started by Danny’s father Jimmy back in the early 1920s, when it began as the Exchange Toffee Works.