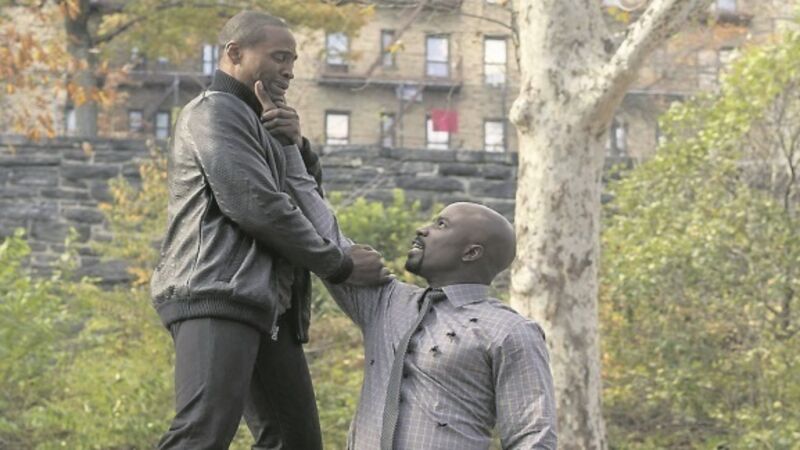

Mike Colter is the first African-American superhero to anchor his own franchise as Luke Cage

LUKE CAGE is the latest stylishly gritty comic book drama from Netflix and Marvel. But the 13-part series also represents a significant television moment, with its eponymous main character the first African-American superhero to anchor his own franchise. In the year of Donald Trump and Black Lives Matter, that’s a big deal.

“I could sit around thinking about what all this means — how it’s a privilege and an honour,” says the show’s low-key star, Mike Colter, when the Irish Examiner meets him in Paris.

“I try to deflect things like that. We’ve been having this conversation for a long time. Was there ever a moment minorities felt they was ample representation? We are in a diversity age. I talk about the lack of diversity for black Americans, but what about the Asian Americans? You don’t see them very often.”

Luke Cage was created in 1972, at the height of the blaxploitation craze. Marvel’s attempt to cash in on the trend was well intentioned but also crude (the writers and artists were of course all white). In his early incarnations, Cage wore a bright yellow jumpsuit and his patter felt like a creaking parody of seminal blaxploitation films such as Shaft (his catchphrase was “Sweet Christmas”).

[media=youtube]https://youtu.be/ytkjQvSk2VA/media]

The Netflix adaptation is very different and, in its early episodes, is closer tonally to gritty crime dramas such as The Wire than to the cheesy Age of Ultron or Ant-Man.

Credit for this goes to show-runner Cheo Hodari Coker, a former hip hop journalist and biographer of the rapper Notorious BIG (in a wink to Coker’s previous career, a portrait of ‘Biggie’ hangs in the study of Luke Cage’s nemesis Cottonmouth).

“I’ve watched the Marvel movies,” says Colter. “They’re enjoyable as family entertainment. I understand how it appeals to people. It’s not stuff I would watch himself.”

Indeed, he would probably have turned down Luke Cage had it been a more conventional — ie over the top — costumed affair. Instead, Cage is here presented as a regular dude who just happens to have bullet-resistant skin and incredible strength. There is no Lycra or pungent dialogue.

“That’s where I would have drawn the line,” says Colter of the prospect of squeezing into a jumpsuit. “I don’t think I would have done it. Something that might show an outline of my manhood is not on.”

Colter’s incarnation of the character had his debut in last year’s Jessica Jones series, also from Netflix. By the end of Jessica Jones he has fled Lower Manhattan for Harlem where he is seeking to keep a low profile. However, against his will he is drawn into conflict with local godfather Cottonmouth (House of Cards’ Mahershala Ali).

As the dastardly Cottonmouth, Ali cuts a conflicted and contradictory figure. The character doesn’t regard himself as evil. He’s just a striver doing his best in an unforgiving world.

“It’s more a reflection of real life,” says Ali. “It makes the material better. The audiences have seen so much now — people are savvier. You have to write for them in a way that is acknowledges that sophistication yet is still entertaining.”

He says he learned a great deal appearing on House Of Cards alongside Kevin Spacey, whose Frank Underwood is one of the great TV villains of the past decade.

“People like Kevin or Ryan Gosling or Brad Pitt, whom I’ve all worked with… they are successful for a reason. The one thing that is unique about Kevin Spacey, apart from Matthew McConaughey perhaps, is that he is the hardest working person I’ve been around. It reminds me to approach what I do without any excuses and expect myself to do the best I can.”

Harlem is rising. #LukeCage pic.twitter.com/Rg13hUpgai

— Luke Cage (@LukeCage) September 30, 2016

Luke Cage doesn’t leap from tall buildings or zoom around in a rocket-propelled car. Instead his power is muscle. He can take a direct hit from a bullet, and in one memorable early scene wrenches a car door off with one hand and uses it as battering ram. Consequently, Colt was required to bulk up for the role, which he found a chore.

“It’s something I don’t necessarily care to do. I’ve got to put the weight on and I’ll find myself in the gym bored. It’s like, ‘Someone put me out of misery’. I try not to eat bread. I don’t drink a lot of alcohol. These are things you sacrifice because if you don’t you just make it harder for yourself later on.”

Colter does sometime wonder if we have reached ‘peak superhero’. He suspects not. As long as there is an audience for stylishly shot mayhem, the boom will continue.

“It’s almost like saying are we content with enough gun violence on screen or will ever get sick of sex scenes? You change the positions and it becomes appealing. If we don’t find those things entertaining, what’s left? Maybe we’ll go back to books.”

Luke Cage touches on hotwire issues such as gentrification and police violence. “You go to somewhere like Harlem and the police don’t strike up a conversation with people,” says Colter. “In a well-to-do area, the police will talk to people, learn their names.

“But in a poorer area they never talk to the locals. And then when something happens, they just don’t know them. So instead of this being a guy named John with a kid and a wife, he’s a stranger they’ve never exchanged words with before. It creates needless tension.”

He hope viewers takes to Luke Cage as enthusiastically as they did to Netflix’s previous Marvel forays, Daredevil and Jessica Jones.

However the deadpan Colter won’t be paying especially close attention. That way crippling insecurity lies.

“Some people love social media — they sit there all day long downloading pictures of themselves, exchanging photographs with fans. They love seeing their own work. They love everything about it. It’s a bit narcissistic to me. It makes me sick — what are you doing? Can’t we just be in the moment? Everything has to be captured and shared with fans so they can can ‘likes’. I don’t get it.”