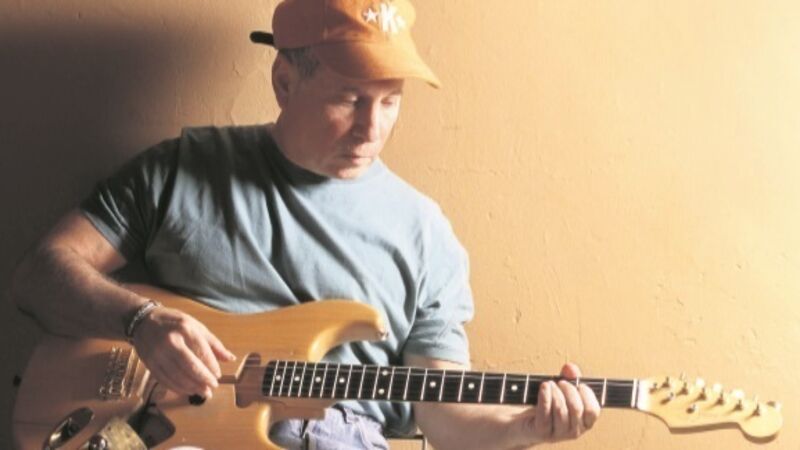

Paul Simon: The stranger on the strings

Paul Simon has never stood still. As he readies Stranger To Stranger, he talks to Andy Welch about his restless spirit, operating with no expectations and why he’s only done when he’s done

Paul Simon was just a teenager when he released his first single.