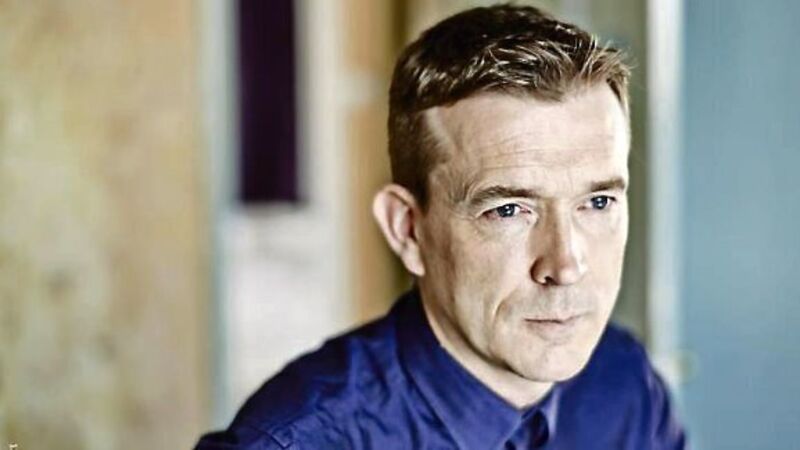

David Mitchell's 'Slade House' - An inside-out ghost story that is frighteningly effective

Thankfully, however, Mitchell seldom limits himself to the normality of realism alone.

It is, in fact, his great strength as a novelist that he so readily marries masterful prose to big ideas such as the sentient satellite of Ghostwritten (1999), the nested narratives of Cloud Atlas (2004), or the vast battle between good and evil which provides the backdrop to The Bone Clocks (2014).