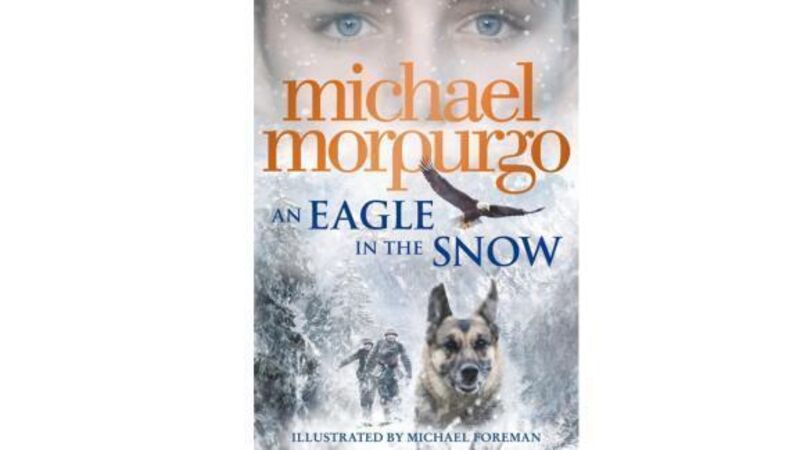

Book review: An Eagle in the Snow

WHEN children’s writer, Michael Morpurgo, was a young middle-class boy growing up in England in the 1940s and 1950s, life seemed very innocent at a time when parents could protect their offspring from the harsh realities of life.

“There was nothing intruding,” says the former UK Children’s Laureate best known for his novel, War Horse which was made into a hit musical and also a film directed by Steven Spielberg.