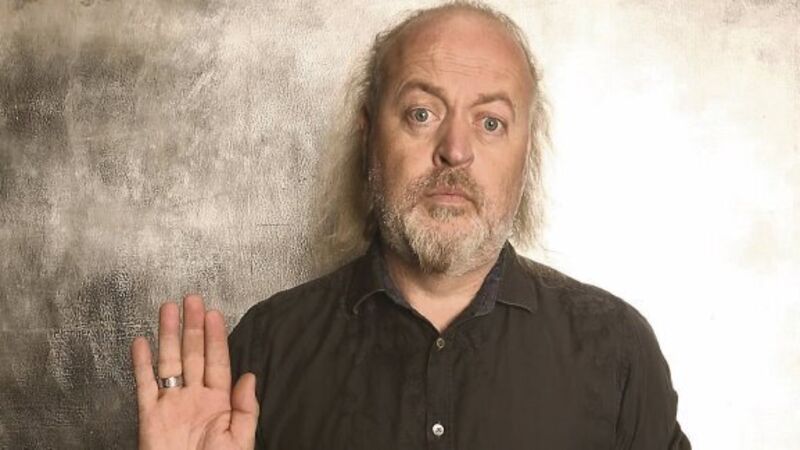

Bill Bailey: Original of the species

ILL BAILEY, due to tour Ireland next month, first visited this country in the 1980s. He came as part of a double act called The Rubber Bishops. “I don’t know what we were thinking,” he says.

“We were performing in cassocks covered in studs and chains. In hindsight, it probably wasn’t the best idea.”