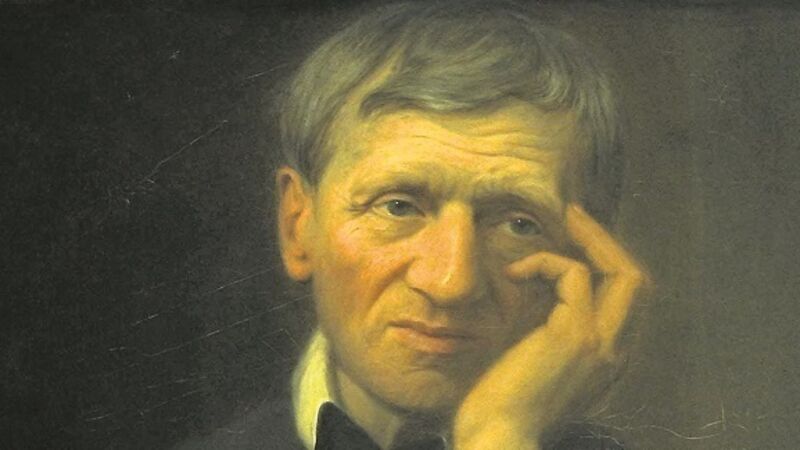

Newman’s vision a degree too far for traditionalists

Beginning with a scattering of buildings in and around Stephen’s Green, Newman’s job was to set up an institution from scratch, one that would flourish in its own right but also rival mighty Trinity College down the road and see off the challenges posed by the newly-formed Queen’s Colleges in Dublin, Cork and Galway.

The new university would be filled with men from Ireland and abroad, including English converts like Newman himself. Women were not yet part of the conventional idea of a university.