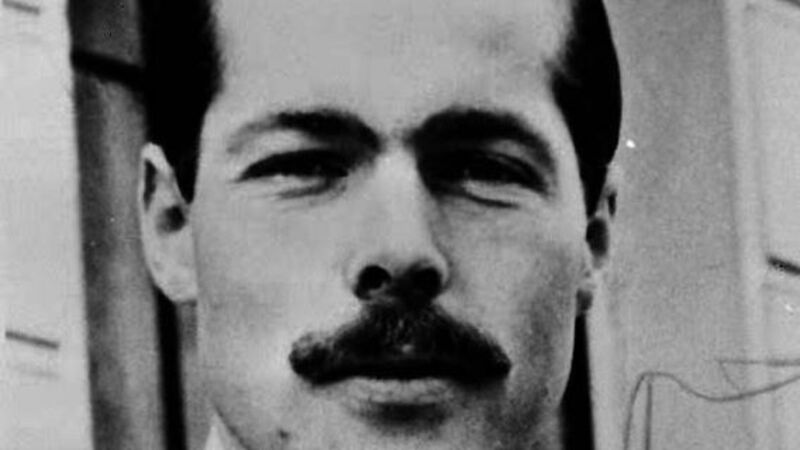

New book on Lord Lucan offers a killer punchline

NOTHING fascinates like a good murder. Public interest in a grisly demise is insatiable and literature, cinema, television and news media all respond accordingly.

All the better if the murder is real, but bears the hallmarks of fiction — larger-than-life characters, doomed love affairs; a status, class, or rank well above the common low-life associated with such ghastly goings-on, and a chief suspect who has vanished into thin air.