Chronicler of life in China now has an audience in the West

IN LATE 2012, the Swedish Academy surprised the literary world by announcing China’s Mo Yan as the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature.If he was known to western audiences it was for the 1987 Chinese-language film adaptation of his novel, Red Sorghum, which won the prestigious Golden Bear Award at the Berlin Film Festival. The Nobel Prize has catapulted him to international prominence.

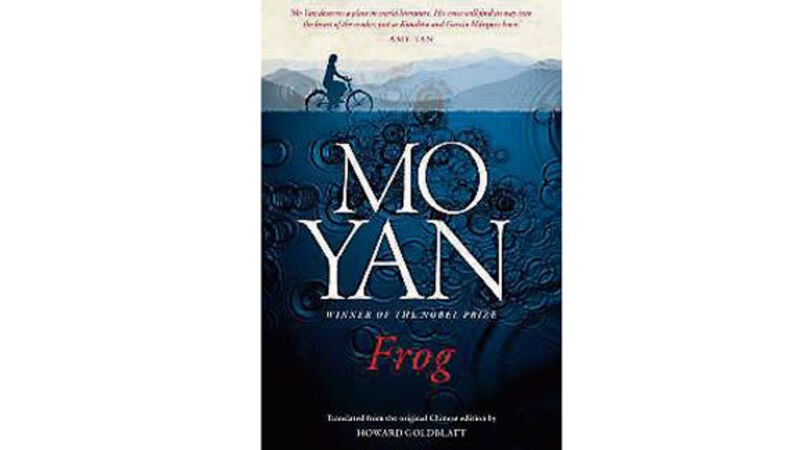

Frog, his eleventh novel, is narrated by Wan Zu (also known as Xiaopao, or by the nickname, Tadpole), an aspiring writer. Across five sections, the last of which is a nine-act play, and with each section introduced by a letter to his mentor, a successful Japanese writer, Tadpole unfurls the story of his family and his country, during the second half of the 20th century, with a focus on his remarkable aunt, Gugu.