Meet the Irish teen girls who love coding

PHYSICS, chemistry, technology, honours maths — if you heard they were the favourite subjects of a robotics and CoderDojo fan named Kevin, you would consider it normal.

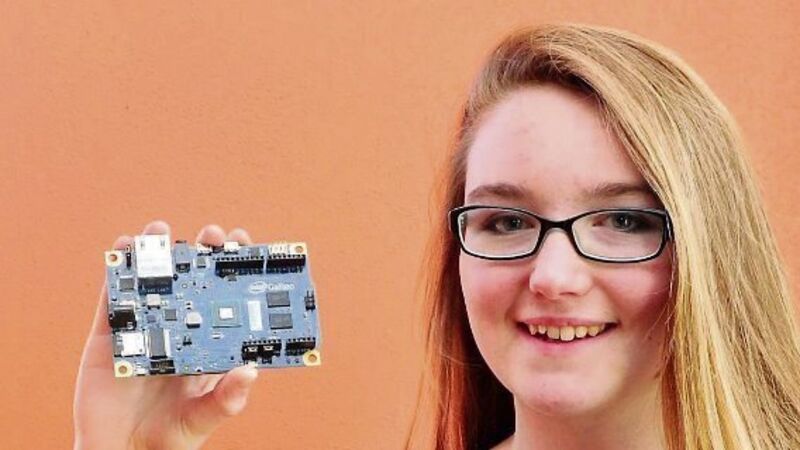

But if that fan was Kate and not Kevin, you’d probably sit up fast. Earlier this year, teenager Kate O’Donovan worked for several months on a robotics project in her local CoderDojo in Clonakilty (free weekly clubs where basic programming is taught through peer learning in a sociable environment).