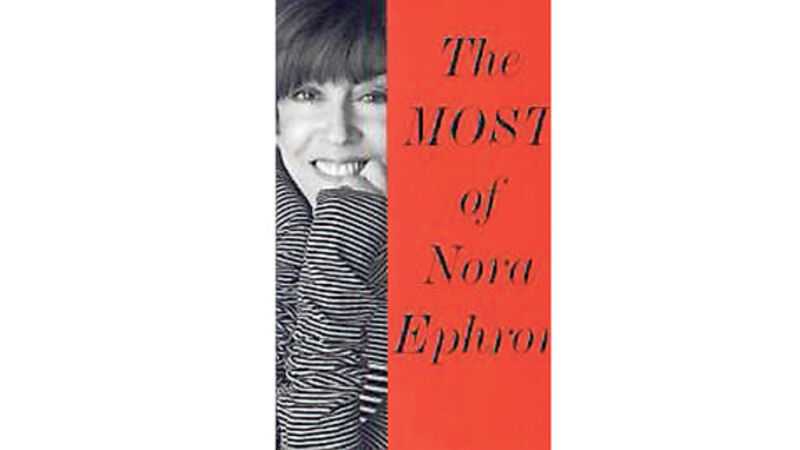

A sharp wit and a sassy attitude

Doubleday, €18; Kindle, £6.99

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBEThe Most of Nora Ephron

Doubleday, €18; Kindle, £6.99

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Our team of experts are on hand to offer advice and answer your questions here

Newsletter

The best food, health, entertainment and lifestyle content from the Irish Examiner, direct to your inbox.

© Examiner Echo Group Limited