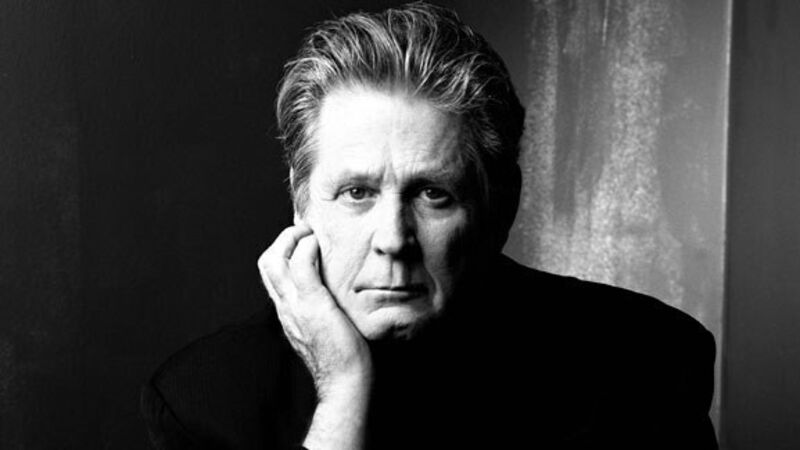

Brian Wilson is stuck between good and bad vibrations

BRIAN WILSON speaks softly, as if alarmed by the sound of his own voice. There are lots of pauses, occasionally he lapses into silence and doesn’t talk again until you prompt him. Wilson, the songwriting force behind The Beach Boys, seems melancholy, a little confused at times — a person with one foot in this world, one foot somewhere else.

“I’ve been working on my autobiography,” Wilson, 71, tells me. “I do interviews with my book writer. It brings back bad memories. There are good memories too. But lots of tough ones. I have to get through that, so I can move onto talking about something happy.”