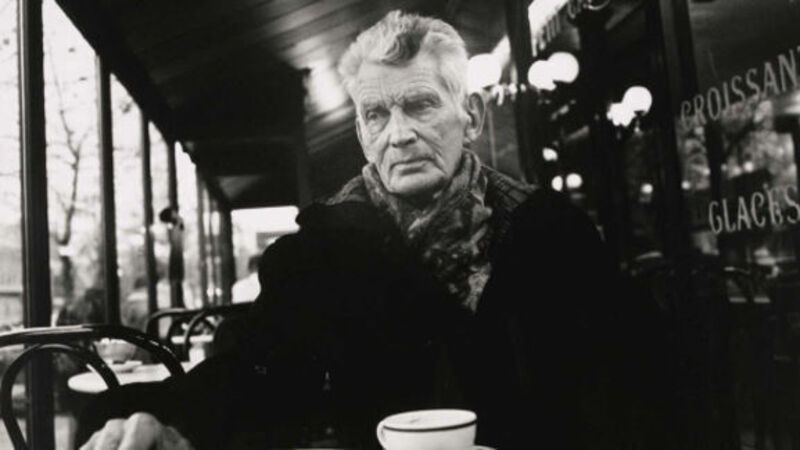

Samuel Beckett: A light that never goes out

SAMUEL Beckett died in 1989 at the age of 83. I was always very close to him as a friend as well as an author and was privileged to publish him from the time I met him, shortly after the first London performance of Waiting for Godot, which only Harold Hobson had reviewed favourably in his Sunday Times regular column. Hobson had gone back several times to review it again, which led to other drama critics going back to see it again and change their minds about its merit.

I came to know Beckett as a man of great learning which he modestly concealed. He was also a great conversationalist, willing to stay up talking until late in the night on a variety of topics, from the day’s news to the things that interested us both, such as literature, music and painting. He enjoyed his wine, which accompanied a small appetite, but he also was not averse to an Irish whisky.