Laughing at the race lines

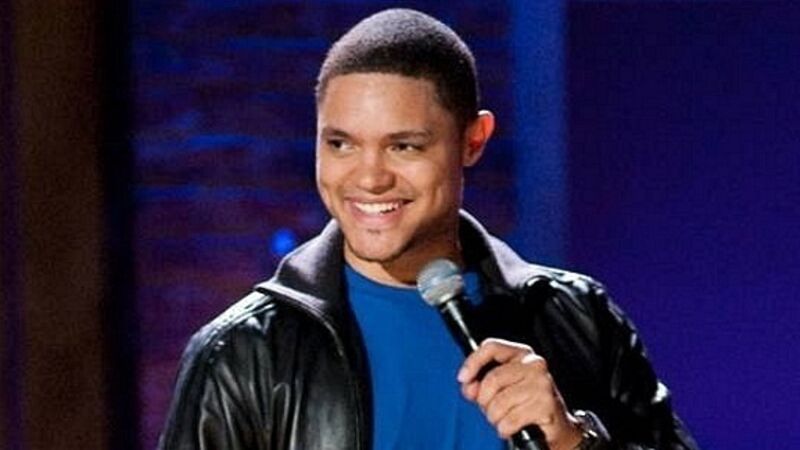

SOUTH Africa’s most popular comedian Trevor Noah brings his show The Racist, which was a big hit at the Edinburgh Fringe last summer, to Vicar Street in Dublin next Friday.

Noah’s mother is from Johannesburg and his father is from Switzerland. They met in Soweto during the apartheid years, when it was illegal for black people to fraternise with whites. His mother was often arrested and thrown into prison at the weekend for her socialising. When she gave birth, she couldn’t tell the authorities the father of her baby was white. As Noah says, he was “born a crime”.