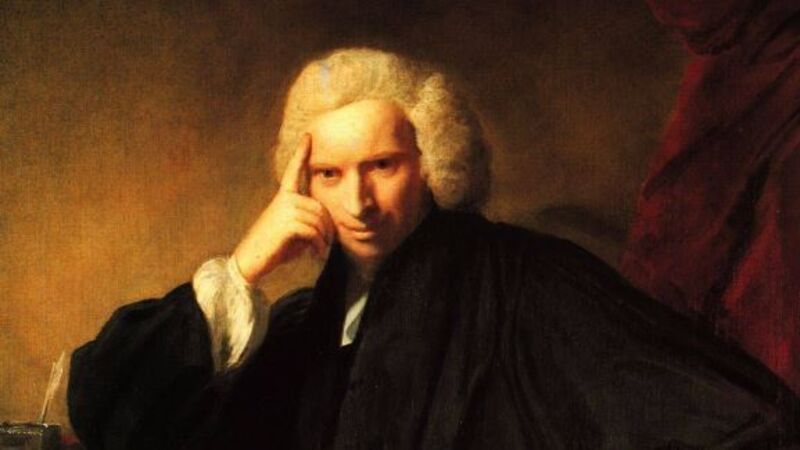

A long way back to Tipp for Tristram Shandy author

Tradition has it that Sterne was born in a house in Mary Street, and later lived in a lane off Clonmel High Street, close to the West Gate.

His father was a British army officer, and during Sterne’s infancy the family stayed in barracks in Wicklow and Dublin. At 10 years old he was taken to stay with his uncle in Yorkshire, and was never to see his father again as Sterne Snr died in Jamaica.